Tips for effective involvement and engagement

To support meaningful and inclusive involvement and engagement, statistics producers can use the PEDRI Good Practice Standards for Public Engagement in Data for Research and Statistics. These standards provide a clear, practical foundation for planning and delivering high quality involvement.

Below are examples of how each standard can be applied in the context of statistics production.

Equity, diversity and inclusion

Engage a broad and diverse range of people, especially those whose data is being used or who are impacted by the statistics. Think beyond typical stakeholders to include underrepresented communities.

Data literacy and training

Provide clear, accessible explanations of the data, methods, and purpose of your statistics. Support public contributors with tailored briefings or training so they can meaningfully take part in shaping or understanding your work. Where possible, show contributors what different options might look like, rather than describing abstract concepts.

Two-way communication

Foster open dialogue throughout your project, not just at the start or end. Enable contributors to ask questions, challenge assumptions, and offer insights into the real-world meaning and use of statistics.

Transparency

Be clear about what data you are using, why, and how. Make sure your engagement activities share information on methodology, limitations, and intended outcomes in a way the public can understand and respond to.

Mutual benefit

Ensure contributors gain something from their involvement, whether that’s new knowledge, influence on outputs, or recognition. At the same time, reflect on how their input improves your statistics’ relevance and quality.

Effective involvement and engagement

Define clear roles for public contributors. Whether they are reviewing questionnaires, commenting on data gaps, or helping interpret results, their involvement should be purposeful, not tokenistic.

Creating a culture of involvement and engagement

Make public engagement a routine part of how your organisation works, embedded in planning, quality assurance, and governance. Build time and support for teams to do it well, not as an add-on.

The rest of this section highlights points that have particular importance for statistics producers:

- Be open about what you are doing, and ask for feedback

- Be clear about your goals for public involvement and engagement

- Be proportionate

- Use existing evidence and ask specific questions

- Systematically record the evidence you gather about opinions, needs and preferences

- Work with others in your organisation for effective involvement and engagement

- Build relationships with communities

- Be honest about the scope of public influence on your decisions

- Be aware of the burden of consultation

- Demonstrate “you said, we did”

1. Be open about what you are doing, and ask for feedback

The baseline for public participation is to publish information about what you are doing, and to encourage (and respond to) feedback. Explain who you are involving or engaging about what you are doing and why, the purpose of their involvement or engagement, and how you intend to use their feedback. Each decision point lists the kind of information it is useful to provide to the public to enable them to provide informed comments.

2. Be clear about your goals for public involvement and engagement

At times it is important to involve or engage the public to understand the lived experience of particular groups, to ensure the interpretation of the data is representative and meaningful to relevant people. For example, you might want to understand how the terminology or analytical categories you are using land with people who belong to particular communities. Or you might want to factor in constraints people with different characteristics have when completing surveys. Here, you can specifically target people with the relevant lived experience.

At other times you need to involve the public to make judgments about what is and is not acceptable in our society. While we might talk about “the public”, there is no one public. People can have very different opinions about questions like what statistics are useful and whether it is acceptable to reuse data for new purposes.

In these cases, deliberative approaches enable discussion, disagreement, compromise and nuance. Presenting a mini-public with a wide range of evidence and arguments from different perspectives, including from those with lived experience, helps the outcomes of such deliberations to be fair, balanced and legitimate.

Case study 7

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is trying to encourage people to complete social surveys online. Participants receive letters through the post, and are asked to access the survey on the web. Some studies are longitudinal; engagement between survey waves can keep up interest and reduce attrition.

The ONS has used a variety of user research approaches to explore the design of contact letters, leaflets, calling cards and envelopes, and the impact these had on participation in surveys. These research techniques included interviews with both participants and interviewers; focus groups; workshop exercises; alpha and beta testing; cognitive testing; and pop-up (guerilla) testing. The results were a set of guidelines on how to design recruitment and survey materials to maximise response and retention through data collection processes.

Source:

Respondent engagement for push-to-web social surveys – Government Analysis Function

3. Be proportionate

It is not necessary to involve or engage the public in every decision you make. Decisions about the level of involvement or engagement should be guided by multiple factors, including the scale of the statistical work, the use of the statistics, the level of sensitivity attached to the statistics and the public interest in the statistics.

Public voice is also only one source of information to guide the production of statistics; expert and technical input is also important. You should not involve or engage the public in a decision if:

- you are not clear about why you are involving or engaging them, or their contribution cannot make a difference to what you do

- you are confident that you already know what the public will say, because there is existing research, you are already receiving feedback, or there is a clear message from public discourse

- you are at risk of straining relationships with the communities you want to consult with because of the burden you are placing on them, and you haven’t been able to demonstrate their impact from previous engagement

On the other hand, you should involve or engage the public if:

- you have a pressing question that you cannot or should not answer, either because you lack the necessary lived experience or because you are unable to make a balanced assessment of social acceptability of a course of action

- you want to build trust with particular communities by demonstrating that you are involving them and listening to them

The methods you use to involve or engage the public – and the resources you use – should also be proportionate to the scale of the question you are asking. Consultations on wide-ranging questions or topics that require deep consideration need more time and resources than small queries about the wording or presentation of statistical outputs. For example, the England and Wales Census 2021 consultation summary webpage states that numerous activities occurred between 2013 and 2021 to seek public views on different aspects of the Census. In contrast, understanding attitudes towards small changes to a publication may only require a couple of days reviewing existing evidence and running a single engagement exercise to gather opinions about the specific output.

4. Use existing evidence and ask specific questions

General public attitudes research already tells us a lot about what the public think about data and statistics, but the context and details matter. The more concrete and specific your questions are, about areas where you genuinely want to better understand the public, the more useful their involvement is likely to be.

For example, Design Lab participants highlighted that, in general, people want statistics to:

- reflect and be relatable to their experience

- use plain English, and appropriate language and framing

- be easy to find and understand

and that this can involve:

- providing different levels of detail, and different output types (such as charts, tables and text) for statistics

- partnering with (news) media, influencers and other intermediaries to share statistics

- having a succinct methods and summary information rather than something too overwhelming

Harmonised standards and guidance provide a useful, well-researched baseline for data collection and presentation, but different statistics may need to reflect different experiences, use different language, and have different routes for discovery and communication. These are the kinds of topics it is worth asking relevant publics about for particular statistics.

Similarly, the ONS has brought together existing public attitudes research on acceptable and unacceptable uses of and handling of data. The 2024 Public attitudes to data and AI Tracker survey states:

Increasingly, the public agrees that data use is beneficial to society and recognises the useful role data can play in designing products and services that benefit them. However, while public attitudes regarding the value and transparency of data use are becoming more positive, concerns around accountability persist. Anxieties are primarily rooted in data security, unauthorised sales of data, surveillance, and a lack of control over data sharing. These concerns are particularly prevalent among older individuals. Notably, these issues mirror the themes participants recalled hearing about in news stories.

But, again, different types of data and statistics will bring different benefits and risks to different publics, and varying levels of trust in the organisation collecting and analysing data can have a big impact on what is judged to be acceptable. The more context-specific the question, the less likely you are to get the answer “it depends”.

Highlighting the existing evidence you are building on when engaging with the public saves them from reiterating things you already know and helps them feel that the engagement is meaningful and additive.

5. Systematically record the evidence you gather about opinions, needs and preferences

Whether your insights come from reviewing existing evidence or engaging the public directly, a clear and agreed approach to recording opinions, needs and preferences is essential. Maintaining a clear record of this helps you demonstrate responsiveness, track how public voices have influenced your work, and provide transparency to the public and wider stakeholders. This record should be regularly reviewed and updated as new insights emerge, ensuring that public perspectives are not only heard but actively inform decision-making throughout the lifecycle of your statistical products. A clear record also supports the “you said, we did” approach (described in tip 10), helping to close the feedback loop and build trust.

There are numerous ways that you can record public perspectives, such as by following user or social research approaches to logging user needs:

- Writing user needs statements: Producing statements in a set format such as, ‘as a [characteristic], I need [something], so that [desire, outcome, or goal]’

- Creating personas: Developing fictional, evidence-based descriptions of a type of person or group that sets out who they are and explain needs, motivations and barriers

- Journey mapping: Visualising the experience a person has with a statistic, and setting out specific needs for each stage

- Thematically analysing needs: Grouping needs by themes, with information about who expressed them and where possible why

In some instances, it may be valuable to take your record of needs back to public contributors to get their perspective on how their views were captured and reflected in your output. Public contributors can also be involved in developing this record, for example through co-creation sessions where you work together to identify themes.

6. Work with others in your organisation for effective involvement and engagement

Involving or engaging with the public takes time, resources and expertise, and its scale should be relative to the impact and importance of the statistics. As a statistics producer, be practical about where those resources are most usefully spent and try to work with other people in your organisations around engagement.

For example, can you get people running your surveys to ask a few additional questions of the people they are engaging with? If data is being collected through surveys administered by interviewers, you could ask those interviewers for their observations about which parts of the survey people struggle with. A similar approach could be used to gather information from call centre personnel supporting people to complete online forms.

Communication professionals may be able to support monitoring of conversations that are already happening that can inform statistics production. For example, they could help you understand what is needed and what public concerns are, by answering questions such as:

- What is being said in traditional and social media about the topic? What research and statistics are being cited? Who is using this information?

- What are common areas of misinformation and are fact checkers able to draw on statistics to support their activity?

- What are people saying directly to your public body, through online comments, requests or team inboxes, about your statistics?

That said, bear in mind that public discourse and individual comments may not be representative.

7. Build relationships with communities

Building relationships with communities and civil society organisations over time can help to create understanding and trust that means questions can be answered or issues addressed quickly and effectively. Where there is clear benefit from involving members of the public in your work, or groups that represent the public, you might consider how you can enable enduring communication channels. This could be by expanding statistics user groups or running parallel groups that include survey respondents and those most likely to be affected by decision making informed by your statistics.

8. Be honest about the scope of public influence on your decisions

The public rarely has the final say over statistics, which also have to satisfy internal needs, constraints and limitations, as well as ministerial priorities. As outlined in the Code of Practice (particularly under principles 2: lead responsibly, and 8: be relevant) producers of statistics hold responsibility for making decisions that balance these requirements, and ensuring users are at the centre. To engage responsibly, it is important to clearly state which aspects of decision making the public can influence, and to explain why some elements are not open to input.

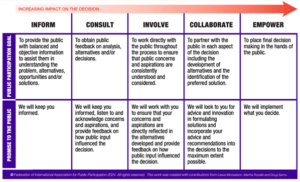

Over-promising about the influence the public has undermines trust. Use the spectrum of public participation (Figure 1) to identify your goal in involving the public and what promise you are making to them about the consequences of that involvement. You may find you need to engage people earlier in the process to have their input be more meaningful within it. This will require factoring in time for people to share their thoughts, as well as ensuring there is time for you to act on the feedback you receive.

Figure 1: The IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation

Members of the public may not always be fully aware of the complexities, constraints, and trade-offs involved in producing official statistics. Rather than viewing this as a barrier to, or a reason to substantially limit the scope of, engagement, there can be value in open conversation about the dilemmas you face. By unpacking these issues transparently (such as through deliberative approaches) you can facilitate a better understanding of the compromises and competing priorities that shape decisions. Such engagement enables contributors to appreciate the realities behind statistics production, fostering trust and encouraging more constructive discussion around the balances that must be struck between different stakeholder interests.

9. Be aware of the burden of consultation

Different people have different awareness, capabilities, motivations and constraints on their engagement with public bodies. For example, even the timing of engagement activities (e.g. during working hours, or at school-pick-up time) can limit who can be involved. Every method for engagement has limitations; aim to be as inclusive as possible and consider using a mix of approaches to fill the gaps.

Efforts to be inclusive can mean that some groups shoulder a proportionally greater burden around consultation, leading to consultation fatigue. For example, it is important to engage with disabled communities to ensure statistics reflect their experience and are accessible for them, but this also means disabled communities are called on more than others. You should have an answer when they ask, “what is in it for me?” Remuneration for time spent providing input might be one answer. Ensuring consultation is meaningful, so inputs supplement, rather than replicate, existing evidence and make a difference rather than being tick-box exercises, might be another.

10. Demonstrate “you said, we did”

Try to follow up with people and groups who have provided input and feedback to explain what you have done as a result. This helps people feel heard and that their time and effort to engage with you was worthwhile. There are numerous ways in which you can communicate this information, for example through:

- E-mail updates or project newsletters

- Published reports

- Blog posts

- Follow-up meetings or workshops.

You could also consider publishing “you said, we did” information so that participants can find it even if you lose touch. This also helps other members of the public to understand how the public was involved in your decision making.

In explaining what you did after your engagement, you may choose to set out the criteria that was used in your decision making (such as feasibility, impact, or alignment with strategic goals) and who was involved in the process (such as advisory panels, internal teams, or external experts). This will help to show the part in the process that the participants played, and make it clearer why their suggestions were or were not taken forward.

You do not have to have done everything people said to provide information about how their involvement influenced what you did. There might have been other considerations, such as resource constraints or requirements from other stakeholders, that meant you could not do everything they wanted. Explaining the full decision making process can help to demonstrate the constraints and trade-offs that led to this outcome; these constraints should also be explained during your engagement activities with them. In these situations, reflecting what you heard from participants, and why you chose to do what you did, is enough. If appropriate, you may also wish to explain that the suggestions could be revisited in the future, or to invite the contributors to engage in future activities.

Often when you use external companies to recruit people to take part in your public involvement and engagement activities, you won’t have direct access to them after that activity, to enable follow up. Think about the full cycle of involvement, including follow-up, when you are putting together requirements from external recruitment firms.

Content to consider for your public involvement and engagement plan

Answer the following questions to ensure that your public involvement and engagement is effective. You should describe for each question both what you are currently doing and what you intend to do in the future.

- What information do you publish about statistics production, and what routes are there for feedback about your statistics or production processes?

- What feedback and input have you already received about your statistics, and how have you responded to it?

- What research about public attitudes or user needs are you already aware of and how can you use it to shape your statistics production?

- How might you find and use other existing evidence to understand public views about your statistics?

- What questions (if any) still need public input, and what level of public participation will you be engaging in around them?

- Which people, communities, civil society groups or other intermediaries do you routinely engage with (if any) and how?

- What steps are you taking to ensure public involvement and engagement is inclusive and worth participants’ time and effort?

Which other teams do you work with to help you involve and engage with the public and how?