Findings

Embedding intelligent transparency

There has been good progress embedding intelligent transparency within ministerial departments and devolved governments since our campaign began.

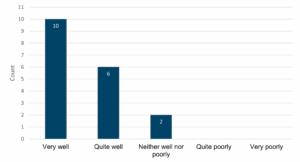

Awareness and understanding of intelligent transparency are high among statisticians and other types of analysts. We carried out a survey of Heads of Profession for Statistics and Chief Statisticians within the 20 departments and governments in scope for this review and received 18 responses. Heads of Profession and Chief Statisticians were asked to rate how well they considered the principles of intelligent transparency were embedded among different groups within their organisation: very poorly, quite poorly, neither well nor poorly, quite well or very well. Most respondents reported that among statisticians, the principles of intelligent transparency are embedded either very well (10 out of 18 respondents) or well (6 out of 18 respondents) within their organisation (see Figure 1). No respondents reported intelligent transparency being quite or very poorly embedded among statisticians.

While this is a self-reported measure, it strongly supports similar findings from our engagement with statisticians during regulatory work and our previous ‘state of the statistical system’ reviews. In our 2024 State of the Statistical System report, we found that government departments were increasingly following the principles of intelligent transparency by making underlying analysis available when figures were used in public statements.

This followed our 2023 State of the Statistical System report, which found that the statistical system was demonstrating a greater understanding of the need for intelligent transparency and highlighted a variety of approaches being taken to minimise the risk of unpublished figures being used in the public domain. These examples included embedding analytical teams within private offices, setting out agreements on the use of statistics with departmental communications team, and providing training on the use of statistics to the wider department. However, we noted in our 2024 report that concerns were still being raised with us regarding ministers and other government officials publicly quoting unpublished figures or figures that lack context.

Figure 1. How well or poorly embedded are the principles of intelligent transparency with statisticians in your department?

Heads of Profession for Statistics and Chief Statisticians themselves have also become strong champions for intelligent transparency. Heads of Profession were some of the strongest supporters for introducing intelligent transparency to the third edition of the Code. They have also been instrumental in developing and implementing guidance, providing training and embedding processes to support intelligent transparency within their organisations. All the departments and governments in scope of this review now have some form of guidance, training and/or processes relating to intelligent transparency in place. Specific examples of these are detailed in three case studies later in this report.

The success of embedding intelligent transparency within organisations relies on everyone, not just analysts and statisticians. We have seen some improvement in the awareness and understanding of intelligent transparency among communications professionals in the last couple of years.

OSR has worked closely with the Government Communication Service (GCS) to raise awareness of the Code and intelligent transparency. We have jointly developed training modules on communicating statistics and intelligent transparency as part of the GCS Advanced training modules. OSR has also presented on intelligent transparency at the weekly GCS call and to communication teams within departments and governments including HM Treasury, Defra, the Department for Education and the Scottish Government. Finally, OSR’s Director General for Regulation was also joined by the Head of Government Communications at the 2024 Government Statistical Service conference, where they gave a joint keynote session on the importance of communications and analytical professionals working together to build public trust in statistics through intelligent transparency.

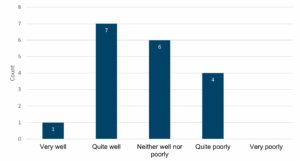

However, we found in this review that awareness and prioritisation of intelligent transparency among non-statisticians, particularly beyond the analytical professions, is variable and generally not as good. In our survey, fewer than half of respondents reported intelligent transparency being very (1 out of 18 respondents) or quite (7 out of 18 respondents) well embedded beyond statisticians (see Figure 2). Most respondents reported that intelligent transparency is either quite poorly (4 out of 18 respondents) or neither well nor poorly (6 out of 18 respondents) embedded.

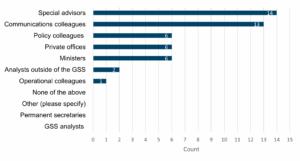

The most common groups that respondents identified as requiring the most support with intelligent transparency were special advisers, policy colleagues, private offices, ministers and, despite the progress described above, communications professionals (see Figure 3). In our conversations with stakeholders, economists were also identified as a specific group within the analytical professions which may require more support. Some stakeholders told us that in their experience, although awareness of the concept of intelligent transparency may be lower among these groups, most colleagues do understand the need for it when it is explained, and active resistance to implementing the principles is incredibly rare. This points to a need for initiatives to proactively raise awareness and support the implementation of intelligent transparency across professions, which we discuss in more detail in this report in the section on training and guidance.

Figure 2. How well or poorly embedded are the principles of intelligent transparency in your wider department?

Figure 3. In your department, which of the following groups do you believe require the most support with intelligent transparency?

There is also variation in how successful the embedding of intelligent transparency has been across different ministerial departments and governments. We heard from stakeholders that each organisation experiences its own unique set of challenges. Factors which influence this include varying levels of resource for analytical work, varying pressures to work at pace and the nature of the topics covered by departments, for example those that are of high public interest or are highly sensitive.

At OSR, we see this variation evidenced by requests for more support from us by some organisations compared to others. We also see varying rates of issues relating to intelligent transparency raised with us, for example through our casework. However, we do note that patterns in our casework can reflect topics which are of high public interest at a certain point in time, or of interest to individuals who contact us, rather than reflecting how well embedded intelligent transparency is within an organisation.

In the following sections of this report, we consider each principle of intelligent transparency, setting out our findings and recommendations for improvement.

Equality of access

Equality of access is at the very heart of intelligent transparency. For the public to be able to scrutinise claims and decisions which are made based on analysis, that analysis needs to be available to everyone. The Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis state that, where possible, public communications should draw on the latest and most reliable published official statistics. When this is not possible, the relevant analysis should be published in advance of use in public communications and separately from related policy and ministerial statements – for example, in what is referred to as an ‘ad hoc release’. If unpublished statistics, data or wider analysis are referred to publicly, they should be published as soon as possible afterwards, ideally on the same day.

Collaboration across professions

In order to achieve equality of access, it is essential that colleagues work together across professions. This is because many different people are involved in the preparation and use of analysis – from those producing the initial analysis, to communications professionals, to those working in private offices who are directly briefing ministers.

Stakeholders told us that strong relationships and collaboration between professions can be a key facilitator of the implementation of intelligent transparency. To facilitate this, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has embedded an analyst within its private office. This lead analyst acts as a key point of contact, ensuring awareness of wider analytical activities and adherence to the Code. More information about DWP’s activities to embed intelligent transparency are detailed in a case study later in this report. Finally, we also heard from stakeholders about the positive impact that strong support from senior leaders, such as permanent secretaries and directors of communication, can have on successfully embedding the principles of intelligent transparency. We discuss this topic again later in the section on Decision making and leadership.

While good collaboration is a key facilitator to embedding intelligent transparency, poor collaboration between professions can cause issues. For example, we heard from stakeholders that a lack of engagement between analysts, private offices and communications or policy professionals sometimes made it more challenging to achieve intelligent transparency. In some cases where issues with adhering to intelligent transparency had occurred, stakeholders highlighted that this was due to no analysts being involved before a figure was used in a briefing or publication. Some stakeholders reflected that changes in departmental structure to bring relevant teams into one directorate had made a positive impact on this. Clearly defined processes which require analytical advice to be sought when figures are used in briefings and publications have also helped some organisations to improve collaboration between professions.

Publishing ad hoc releases

In some situations, if the analysis to support a planned publication or public statement is not already in the public domain, an ad hoc release will need to be prepared and published in advance. This can place additional pressure on analytical and publishing staff within organisations. Stakeholders told us that limited resource to deliver ad hoc releases and explainers can be a barrier to implementing intelligent transparency. This barrier is most prominent within departments with small official statistics functions, such as the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, or those with a large breadth of analyses across various topics and by various producers both within and outside of government, such as the Department for Transport and the Department for Health and Social Care.

We also heard that where the analysis being published in an ad hoc release is not a clearly defined type of analytical output (for example, official statistics, research or policy evaluation), there can be no clear mechanism to ensure that the analysis is published in a timely way. This was a barrier previously experienced by the Department for Transport (DfT). To overcome this barrier, DfT agreed and internally published guidance on the publication approach for this scenario. Once analysts have determined that the use of a particular figures in a public statement is appropriate, supporting material in the form of a background quality and methodology note is prepared and published. This new process has been endorsed by the chief analyst, chief press officers and the DfT publishing team, and has meant that the department can focus on transparency rather than spending time on the logistics of publishing analysis.

Engagement with Number 10

Some stakeholders identified ‘grid slots’ and collaborating with Number 10 as occasional barriers to publishing ad hoc releases to support the public use of statistics, data and wider analysis. The ‘grid’ is used by Number 10 to plan government announcements and publications, and a slot on the grid can be the main mechanism available to ministerial departments for ad hoc publications. In practice, a slot can be challenging to obtain, particularly when there is a deadline by which analysis should ideally be published.

We have found that there is a good understanding of the requirements of the Code and intelligent transparency within the analytical team at Number 10. This includes the Number 10 Data Science team (known as 10DS) which regularly engages with data teams across government. However, stakeholders also told us that in their experience, awareness and understanding of these can be relatively low among special advisers and those responsible for the gridding system. As there is no Chief Statistician or Head of Profession for Statistics within Number 10, statisticians in other departments do not always know who to contact to discuss issues relating to data and statistics. Stakeholders told us that this can exacerbate challenges when trying to identify grid slots for publications or resolve issues about the use of unpublished data in the public domain.

Recommendation 1:

To support equality of access to statistics, data and wider analysis, Number 10 should review and act on training needs on the Code of Practice for Statistics and intelligent transparency for special advisers and those responsible for the ‘grid’. It should also improve connections with the statistical community across government so that issues can be identified and resolved promptly. For example, it may be beneficial to introduce a Chief Statistician role within Number 10, or for relevant colleagues within Number 10 to make links with the Head of Profession for Statistics network by joining their regular mailing list and meetings.

Supporting understanding

Once statistics and data are in the public domain, it is crucial that they are communicated and used with integrity, clarity and accuracy. This allows the public to understand the basis for claims and decisions made, in turn supporting understanding of key societal issues, including the impact of policy. The Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis state that public communications should be clear about where figures come from, for example, by citing sources in publications and on social media.

Citing sources

Through our regulatory work, we are aware of several examples where sources have not been cited for numbers used in government publications such as press releases, blogs and infographics shared on social media. To better understand the scale of this issue, we carried out a manual check of all press releases published by ministerial departments and devolved governments between 14 July and 20 July 2025. We reviewed each press release to identify references to statistics, data and analysis, and to determine whether a source was cited (for example, named in the main text or in footnotes) and whether a link to the source was provided. It is important to note that if a citation and/or link to the source was not identified, this does not necessarily mean that the underlying analysis is not published. Annex C provides a summary of our review.

We identified 80 press releases published during the week beginning 14 July. Within these 80 press releases, there were 209 references to data or statistics. Of these 209 references, only 36 (17%) cited the source and just 18 (9%) provided a direct link to the source. The citing of sources is fundamental to intelligent transparency and is now a core expectation of the Code – this is because it enables the public to easily access and scrutinise the supporting information behind figures and the decisions and claims made based on them. Given its importance to achieving intelligent transparency, we want to see an increase in the proportion of figures which cite and provide a direct link to their source in government press releases and other types of publications. At OSR, we are working on ways to monitor progress on this, including the automated checking of government publications.

During our review we spoke to several communications professionals, including members of the central Government Communications Service (GCS) team. They identified that citing sources for figures does not form part of standard practice when publishing communications materials such as press releases and blogs, but that in practice this should be a straightforward improvement to implement. As the GCS refreshes its professional standards, we will be pleased to work with it to ensure that citing sources is embedded as good practice.

Recommendation 2:

To support public understanding of figures and ensure adherence to the Code of Practice for Statistics, all statistics, data and wider analysis used in public communications by ministerial departments and devolved governments should cite a source and directly link to that source. To support this goal, the Government Communication Service should embed expectations about citing sources within its refreshed standards and guidance for communication professionals and clearly communicate these across its networks.

Preventing misuse

The Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis state that public bodies should not use figures in a misleading way, for example by cherry-picking figures, taking them out of context or placing undue certainty on them. The standards also require public bodies to clearly communicate any key context and limitations associated with statistics, data and wider analysis to help the public understand and interpret them.

In order to monitor its own use of statistics, the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) has a well-established ‘control of statistics’ group. The group meets monthly and includes representatives from analytical and communications teams to monitor the public use of statistics by DBT. The group identifies, rectifies and maintains a log of any errors related to statistics and data that are made in public communications (for example, in ministerial speeches, departmental press releases or on social media). This allows DBT to understand if there are common themes in the errors and, if so, to develop and target internal guidance on the use of specific statistics. The group also promotes best practice in the communication of statistics and analysis. More information about this group and DBT’s other activities to promote and embed intelligent transparency can be found in a case study later in this report.

We did not identify any other examples of producers proactively monitoring their own use of statistics, data and analysis in the public domain during our review. While there may be other ways to effectively prevent and address misuse or misinterpretation, we consider that the approach used within the Department for Business and Trade provides a good practice model that others can learn from.

Recommendation 3:

To prevent and promptly address misuse or misinterpretation, ministerial departments and devolved governments should proactively monitor their public use of statistics, data and wider analysis.

Decision making and leadership

The third and final principle of intelligent transparency is about how statistics, data and wider analysis are prepared and published, and who is involved in these processes. The Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis state that public bodies should seek and use impartial, expert advice when using statistics, data and wider analysis in the public domain. To ensure that this practice happens, senior leaders are asked to actively promote and embed these standards within their organisation.

Support from senior leaders

As discussed earlier, we identified that support from senior leaders, such as permanent secretaries and directors of communication, can have a significant impact on how well intelligent transparency is adhered to within an organisation. In the departments where there has been strong progress in embedding intelligent transparency, for example in the Department for Education and the Department for Work and Pensions, senior leaders have made their support clear to Heads of Profession for Statistics and actively engaged in efforts to improve adherence to intelligent transparency.

We have also received several private letters from ministers within the UK Government endorsing the importance of intelligent transparency and committing their departments to adhering to its principles. Given these expectations now form a core part of the Code, and to increase transparency, we consider it important that these commitments are expressed publicly by all departments and governments. This would make the importance of adhering to intelligent transparency clear to everyone in the organisation and provide strong support for Heads of Profession for Statistics and Chief Statistics in their work to ensure compliance with the Code.

Recommendation 4:

To increase transparency and build public trust in the use of statistics, data and wider analysis, ministerial departments and devolved governments should publish public commitments to intelligent transparency. This could take the form of a statement of compliance which sets out what steps the organisation takes to adhere to the Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis and how it resolves issues if they are identified.

Training and guidance

Finally, training and guidance are key to ensuring that expectations about intelligent transparency are clear to everyone and that staff across professions know how to adhere to them. Alongside the publication of the refreshed Code, OSR has published guidance on the Standards for the Public Use of Statistics, Data and Wider Analysis. This guidance sets out who is responsible for implementing the standards, and provides practical advice for all those using statistics, data and wider analysis in the public domain. We also regularly deliver training in the form of interactive seminars to government departments and have developed content for different audiences, including statisticians and other analysts, communications professionals and policy professionals. As discussed earlier, the GCS also includes training on intelligent transparency in its Advanced training modules for communications professionals.

In addition to the guidance and training offered by OSR and the GCS, stakeholders identified that department-specific training and guidance can be very effective. This is because it can be tailored to be as relevant as possible to the circumstances and challenges that staff within the organisation are working with. For example, the Department for Education (DfE) has developed a suite of guidance aimed at different groups within the department, including senior leaders, ministers, special advisers and communications staff. The guidance provides practical advice on the presentation and publication of statistics and other analysis to support intelligent transparency. To promote use of the guidance, DfE runs monthly knowledge sharing sessions and has online induction materials for new starters.

It is important to note that the development of bespoke guidance and ongoing delivery of training require substantial resource. Respondents to our survey indicated that not everyone has access to additional support for intelligent transparency beyond what is offered by OSR, with some explicitly highlighting that there was no additional guidance or material available in their department. While some departments, including DfE, have well-staffed central statistical teams to support Heads of Profession for Statistics with these activities, this is not the case in every department, and some stakeholders told us that resource pressures can be a barrier to developing bespoke guidance and training materials.

To raise awareness and understanding of intelligent transparency across governments and help ease the pressures of delivering guidance and training from central statistical teams, we would like to see the economic, social research and policy professions include bespoke guidance on intelligent transparency within their professional guidance.

Recommendation 5:

To ensure that knowledge about intelligent transparency is consistent across professions, guidance and training on intelligent transparency should be embedded and promoted amongst the Government Economic Service, the Government Social Research profession and the Government Policy profession.