1. Introduction

This review was written on behalf of the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR). As the independent regulator of official statistics produced within the UK, OSR is interested in finding out whether the public trust official statistics, and how further trust in the statistical system can be built.

The work of OSR is underpinned by the conviction that official statistics should serve the public good. This means statistics should be public assets that provide insight, which allows them to be used widely for informing understanding and shaping action. This vision can only be fulfilled if users and potential users of official statistics consider them to be trustworthy. Trustworthiness is one of the three core principles in OSR’s Code of Practice for Statistics, alongside Quality and Value. This research focuses on the factors that can influence levels of trust and considers how these could relate to building trust in official statistics.

About the author

This research review was written by Holly Rodgers, a third-year PhD student studying Politics and International Relations at the University of Warwick. The project was commissioned by the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) and advertised as a placement via the Economic Social Research Council (ESRC). Holly worked on this project during her 3-month placement opportunity, before returning full-time study to complete her PhD thesis.

1.1 Scope of this Report

This report asks: what is trust?; who trusts?; and how do you build trust? These questions help us to understand whether the public trusts those involved in the production, and communication, of official statistics and what accounts for different levels of trust. These questions are answered through synthesising existing literature, and supported by primary analysis (described in Methodology). Thereafter, it concludes with a series of practical recommendations which can be adopted in order to increase levels of trust, improve trustworthiness and contribute to the overall vision of ensuring that official statistics serve the public good.

This report investigates levels of trust and draws together evidence exploring influencing factors. As the literature and existing studies focusing explicitly on the topic of trust in “official statistics” are relatively sparse – with obvious exceptions including the Public Confidence in Official Statistics (PCOS) survey and a small collation of commissioned surveys dedicated to this theme – this review adopts a wider approach which analyses levels of public trust more broadly. It considers studies which explore levels of public trust in actors and objects involved in the production, or communication, of official statistics. This includes the government; the Civil Service; scientists and experts; journalists and the media; research on communication platforms; and evidence more broadly.

From this broader approach to exploring trust, readers are provided with an overall picture of public trust levels. To support this aim, this review adopts a cross-disciplinary outlook drawing on psychological, sociological and political accounts of trust, and considers a range of models developed within these fields. Overall, this report aims to establish: 1) what is trust?; 2) how is trust earned, and maintained?; and finally, 3) how can the statistical system build trust? To clarify, the first objective is definitional, the second is explanatory, and the third is prescriptive.

1.2 Why is Trust Important?

According to a paper presented in 2011 by the UK Statistics Authority (Aldritt & Wilcock, 2011, p.1), trust in official statistics is important because ‘it affects the utility of the statistics; and utility affects the value to government and society.’ In other words, ‘less trust means less use and less value.’

This centrality, and the likelihood that if the public do not trust the evidence presented to them as official statistics, they are unlikely to use it, means that building and maintaining trust is paramount. In the absence of trust, as the Statistics Commission report (2004) warns, overall decisions will be weakened, because the public may be arriving at conclusions without considering all available evidence.

Focusing on the dual assets of trust and value, the Statistics Commission addresses the question at hand rather succulently: ‘Statistics that are not trusted cannot deliver the same value to society as ones that are’ (2008, p.36). Unpacking this further, the report continues to explain that:

‘Users need to have confidence that statistical outputs are sufficiently reliable in terms of measuring the relevant social and economic characteristics – and that any weaknesses in this regard will be fully explained. Users also need to be confident that the statistical products have not been amended (or concealed or delayed) so as to suit a particular policy or argument. These two components – quality and probity – are central to the concept of being trustworthy.’

To flesh out these two components, this review recommends quality and probity. Quality refers to reliability and to producers’ commitment to be transparent about the limitations of the best estimates that the statistics are able to make. Cautionary remarks and communicating uncertainty are instrumental in this regard. The second criterion, probity, relates to concerns around possible misuse or distortion – in other words, ensuring that the statistics presented are a true and honest account of the situation.

Studies focusing on political probity have shown that increasing levels, which signify higher confidence in the honesty and integrity of political bodies, are associated with increased trust in governments (Martin et al., 2020). Thus, applying the same causal mechanism to the domain of official statistics, it is possible that if probity (confidence in the honesty of producers) increases, trust will follow suit.

1.3 What is Trust?

Before turning to the empirical research and signposting what factors the literature proposes influence trust levels, this report asks: what is “trust”? This is because in order to understand how the UK statistical system can build trust in official statistics, it is first necessary to define trust and explore what drives it.

The first point to acknowledge in this regard relates to the elusive quality of trust. As Paperzak explains, one of the reasons that trust is not automatically granted is because ‘trust cannot be displayed, observed or presented as a thing’ (2013, p.9). The array of synonyms one can transplant in the place of “trust” further complicates the task of settling on a definition. For instance, “confidence”, “reliance” and “belief” are a few examples of how “trust” might be substituted in everyday language. This exemplifies how, by its very abstract nature, trust is a vague concept. This uncertainty may have implications for measuring levels of trust.

This elusive quality is further compounded by the significance of trust, as a variable of interest, across a variety of disciplines and research agendas. Within each of these disciplines, scholars have made efforts to arrive at a definition, or conceptualisation, of trust in order to aid further investigative enquiry.

Reflecting on the state of the field in their recently published Handbook on Trust in Public Governance, Latusek at al. (2025, p.3) postulate that the most commonly applied and thus widely accepted definitions are inspired by Rousseau et al. (1998) and Mayer et al. (1995). To paraphrase the former, trust is based on a willingness to be vulnerable, and an expectation that the other person will perform the requested action. These qualities of vulnerability and expectation are echoed by Mayer et al.; however, an additional feature, ‘irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party’ (1995, p.712), is added to reiterate the importance of relinquishing control in the process of awarding trust to another party.

To provide a fuller picture of these different definitions, and highlight what each respective field offers, contributions are grouped into discipline-inspired research agendas and outlined in the following subsections. In line with this structure, trust is defined as a personality trait; a reciprocal process; a rational, socially desirable objective; and finally, a state of vulnerability. Taking stock of the variety of definitions, it is important to note that they are not siloed, and there is crossover between the thematic trends identified.

1.3.1 A Personality Trait

From the perspective of behavioural psychology, the willingness to trust is viewed as a personality trait, with some scholars characterising trust as a behavioural feature which some people have a disposition towards (Rotter, 1967).

To clarify, this characteristic-based definition is not reductionist in the sense that it presumes that those with a predisposition to trust will display a universal and unwavering level of trust. On the contrary, it refers to a tendency, disposition or inclination towards perceiving others as trustworthy – as opposed to untrustworthy. The distinction between trust and trustworthy is unpacked in the “Trustworthiness” section of this paper. However, as a brief synopsis, trustworthiness is the process of demonstrating one is “worthy” of being granted trust, where trust is the outcome (O’Neill, 2018).

In short, a trusting disposition applies to those who are “more likely” to trust than others, even with limited information. Weber et al. rationalise this by explaining how, to ‘ameliorate the anxiety associated with dependence’ or vulnerability, the prescribed solution is to perceive others as trustworthy (Weber et al., 2005, p.75). This suggests that granting others trust is a reassuring process undertaken to remedy the discomfort experienced from a position of distrust (or from remaining in a state of mistrust limbo).

Further contributions from the field of behavioural psychology help provide a picture of what behavioural traits trust is associated with. Studies of this nature suggest that agreeableness, which is characterised by low levels of suspicion and competitivity, is associated with higher levels of trust. (Mondak & Halperin, 2008). Meanwhile, neuroticism and extraversion are negatively related to political trust (Freitag & Ackermann, 2016, p.718).

This provides a useful starting point; however, it still leaves us wondering whether having a trusting personality influences one’s behaviour. Mayer at al. (1995) proposes that whilst personality traits and predispositions may contribute to initial perceptions, having access to more information (whether the other person is trustworthy or not) can alter inclinations to trust. This is because – based on the expectation that one’s track record provides a reliable indicator of future behaviour – once we gather more information, this can act as a supplement to behavioural propensities.

The notion that trust is decided based on repeated exposure to experiences is a common thread within the literature (Smirnova & Scanlon, 2017). This is inspired by Luhmann’s proposition that ‘familiarity is a precondition for trust and distrust’ and is based on the ‘assumption that the familiar will remain’ (1979, pp.19–20).

Further evidence that prior experiences help to alleviate against the influence of behavioural predispositions can be gathered from Müller and Schwieren’s paper (2020). This paper tackles the question of whether experience surpasses personality traits in the context of a trust game (similar to that developed by McCabe & Smith, 2000), discovering that whilst personality was helpful in explaining the behaviour of player one (high agreeableness was a predictor of likelihood to trust, and high levels of neuroticism led to a lower likelihood of trusting), for player two, there was no such correlation between personality traits and behaviour. This suggests that the likelihood of trusting was a product of the situation (whether or not player one had trusted them) rather than their own personality traits, or predisposition to trust. This would imply that personality traits are important predictors of trust, but they are not the sole determinant in outcomes of trusting behaviour.

Previous studies in this area have pointed to the importance of observable demonstrations of trust. For instance, Deck (2010) showed that, in cases where the first response is kept hidden from the other player, trust reduces. This supports the notion that the process of trust is fundamentally one of reciprocity (as McCabe et al., 2003, show), or, to quote Cohen and Isaac, ‘trust begets trustworthiness and also trust in others’ (2021, p.189). In summation, it seems that personality traits shape initial willingness to trust, but reciprocity can outweigh predisposition.

The studies highlighted in this section would suggest that although personality traits may influence one’s willingness to trust despite an absence of information, this can be moderated through exposure and familiarity. This points to the importance of maintaining an active public profile, showing that recognition and exposure support trust building. It is important to remain mindful that both positive and negative reputational legacies can shape future trust decisions. Thus, it is a prerequisite of this recommendation that alongside seeking avenues of exposure, producers also ensure that they have a trustworthy track record to showcase.

1.3.2 A Reciprocal Process

Building on Müller and Schwieren’s (2020) finding that reciprocity outweighs predisposition, the second definition brings in a social dimension and considers how trust functions as a relationship between two (or more) actors (Cook & Santana, 2020). Highlighting expectations of reciprocity, these accounts consider trust to be an interpersonal process which ‘occurs in a dyadic context, wherein parties voluntarily interact in ways that mutually benefit each other’ (Korsgaard, 2018, p.14).

According to this definition, trust is bidirectional and mutually reinforcing. It is a dynamic process which evolves in response to previous interactions. This facilitates the conceptualisation of trusting behaviour as distinct from trustworthiness, whilst explaining how both reinforce each other through “trust spirals”. These trust spirals highlight the reciprocal relationship between trust and cooperation, defining trust as a pro-social behaviour based on cooperation between actors (Cook et al., 2005).

To breakdown the mechanics of the process: the cooperative behaviour exemplified by X is interpreted by Y as a sign that X is trustworthy; thus, Y is willing to trust X and cooperates in return. This outcome, much like a spiral, or virtuous cycle, is then interpreted by X to signal that Y is trustworthy, and so X is willing to trust Y. According to this account, this cycle continues, and trust is built. It is also worth highlighting that this same process can underpin the escalation of distrust – when avoidant behaviour and distrust are substituted into the process outlined above (Korsgaard, 2018, p.14).

Studies which investigate reciprocal trust often use dilemma games to test the bidirectionality of trust. Within these games, trust manifests in cooperative behaviour. One such study, recounted in Korsgaard’s (2018) chapter dedicated to reciprocal trust, found that experiential knowledge (knowledge gained from previous interactions) significantly predicts mirrored trust outcomes (betrayal, reciprocity or reward) (Delgado-Marquezto, 2015).

Further studies (as cited in Korsgaard, 2018) have also shown that cooperation predicts trust, and vice versa. For instance, Ferrin et al. found that trust and cooperation are reciprocally predicted and showed that ‘perceived trustworthiness and cooperation were spiralling upward over time’ (2008, p.167). According to Ferrin et al., reciprocal trust begins as a ‘conscious decision process’ whereby players simultaneously observe cooperative behaviour, draw conclusions and then reciprocate based on that conclusion. However, as time passes, the process becomes more instinctual and automatic, and interdependent, mutually reinforced spirals of trust are established (2008, p.171). This suggests that repeated expressions of trust, exemplified over a sustained period of time, are necessary to ensure that spirals of trust are able to gain traction.

To apply these studies to an actionable recommendation, one could refer back to the mantra ‘trust begets trustworthiness and also trust in others’ (Cohen & Isaac, 2021, p.189). In other words, according to the reciprocal definition, demonstrating trust is needed to initiate the cycle, to be seen as trustworthy, and to earn the trust of others.

In addition to summarising how trust as a reciprocal process functions, it is also important to reflect upon the shape and direction of the exchange. This is because understanding the trajectory of trust helps identify positive triggers, as opposed to negative ones. The alternative, a “spiral of cynicism” – whereby distrust resulting from one issue can be transposed onto another, and then another, and another – has also been theorised. On this theme, studies have used panel data to show that participants who feel distrust are more likely to believe future claims of misconduct (Dancey, 2012). This suggests that, like reciprocal trust, distrust also holds a perpetuating quality.

Dedicating attention to how these positive and negative triggers have been outlined in the literature, Korsgaard (2018) identifies four main branches: 1) facial features and cues; 2) the mindset of the individual, with fatigue, distraction and low motivation setting a negative course; 3) predisposition to distrust outweighing propensity to trust in group dynamics; and finally, 4) experience and expectation.

At a functional level, the process of reciprocal trust entails expectations: namely, that cooperation will be reciprocated. Focusing on political trust, Brennan (1998) describes how the process of being recognised as trustworthy can exert pressure on rational actors to behave in accordance with these expectations. As a consequence of communicating their intention to behave in a trustworthy manner (in this context, the initial act of cooperation), a rational actor feels compelled to abide. This is because the shame of defecting from the expectation outweighs the cost of compliance.

With this in mind, statistical producers should consider making a public commitment to behave in a trustworthy manner. Communicating this to the public may increase pressure on statistical producers to stand by the commitment and behave in a trustworthy manner in the future.

The studies reviewed in this section suggest that cooperative exchanges build trust, trust is reciprocated by rational actors, and trustworthiness can become an expectation when communicated.

A further implication of subscribing to this definition of trust as a reciprocal process is that trust is awarded on the basis of rational choice calculations (as opposed to an innate inclination or personality predisposition). This is because the decision of whether to signal trustworthiness via cooperative behaviours is, to some degree at least, a rational choice based on utility maximisation: to earn the other party’s trust, and in turn their cooperation. Understanding trust as a rational choice is unpacked in the next subsection.

1.3.3 A Rational Choice as a Socially Desirable Objective

Some scholars have sought to define trust as a rational choice, often using game theory to illustrate their conclusions. These accounts view trust as a cognitive process, whereby the individual calculates the value of trust versus distrust, and makes their choice based on achieving maximum utility. In other words, if the expected outcome of trusting is more beneficial than that achieved by withholding trust, trust will be granted – if not, it will be denied.

Of course, this decision reflects one’s own capabilities and objectives. If the objective one desires can be achieved without the need to expose oneself to the vulnerable process of granting trust, then the rational choice may be self-reliance (the denial of trust). However, if the task is beyond one’s capabilities (time, scope, skillset and knowledge) and one considers the outcome to be beneficial, the rational choice is to outsource these capabilities and trust someone else to deliver the outcome.

Tying this back to official statistics, rational choice suggests that highlighting the benefits of official statistics may increase the public’s willingness to bear the costs of trusting them, and the vulnerability it entails (more details on the risks involved in the process of assigning trust can be found in the section “State of Vulnerability” in this report).

In this respect, the value that official statistics deliver, in terms of understanding the societal context and informing effective policies, should be shared publicly. Making greater efforts to communicate these benefits could help balance the cost–benefit calculation in favour of trusting official statistics.

The notion that trust is a socially desirable attribute should also be factored into these calculations. Conceptualising trust through a rational choice lens showcases the appeal of trust and explains how its status, as a positive attribute, underlies trustworthy behaviour. In other words, one may come to expect the outcome of trust, because rational actors will strive to behave in accordance with the desirable attribute (being trustworthy) as opposed to the deviant, or undesirable attribute (being untrustworthy or distrustful).

Illustrating the role of rational choice, Hardin (2002) introduces the notion of “encapsulated interest”. According to Hardin, trust is driven by two factors: 1) interest in maintaining the relationship into the future; and 2) a desire to secure a reputation as being trustworthy (deserving of trust). In a social community, it is considered advantageous to build relations with others. The possibility of being able to expand one’s social network based on a positive reputation (of being reliable and trustworthy) is conducive to this interest; thus, it is considered to be a rational objective. van der Meer (2010) echoes the importance of a positive track record of prior interactions (reputation) and proposes that predictability, and behaving in line with expected actions, can be an important determinant of trust.

Applying this definition implies that the decision to trust can be the outcome of rational calculation. However, it is important to acknowledge that trust is not always the rational decision. This point can be illustrated by conceptualising trust as a four-way matrix, as depicted in the prisoner’s dilemma (variants of which are often used to illustrate rational choice outcomes).Trusting an untrustworthy player in the dilemma not only means that there is no successful coalition, but also results in greater punishment. In other words, as Riker (1980, p.11) explains, ‘the punishment for not trusting, and for trusting unwisely, is the same.’

This reveals the importance of supporting healthy levels of mistrust, presenting mistrust as a method to avoid trusting unwisely. This possibility that mistakenly granting trust may potentially result in a negative outcome underscores the recommendation of avoiding critical or dismissive statements which paint mistrust as irrational. This can be seen in the sphere of official statistics, where trusting an inaccurate or misleading figure could lead to poor decision making and negative outcomes.

To quote Onora O’Neill’s TED talk (2013):

‘The aim to have more trust is a stupid aim. We should aim to have more trust in the trustworthy, and less in those who are not trustworthy’

1.3.4 A State of Vulnerability

The final thematic trend within the literature highlighted here relates to the notion of trust as ‘an individual’s willingness to accept vulnerability’ (Rousseau et al., 1998). This has been alluded to across the different definitions given above, where vulnerability has been presented as an inescapable side-effect of granting trust. Given the centrality of this premise, it is considered helpful to assign a dedicated section to defining trust as a state of vulnerability, and to consider the implications of this definition head-on.

As alluded to above, although rational choice presents trust as a cognitive process, scholars applying this definition do recognise that the act of trusting requires some aspect of vulnerability. For instance, Coleman makes the case that trust is not a mutual, nor social, exchange. This is because it requires the ‘voluntary action of one party alone, the trustor’; they are the person taking on all the risk if they do decide to assign their trust (1990, p.99). This one-sided vulnerability is also reiterated by Duetsch (1958), who defines trusting behaviour as the risk one takes when they increase their vulnerability in a situation where, if the person granted trust abuses that vulnerability, the trustor would be worse off.

This idea of vulnerability is important as it shifts the onus onto the person granting their trust, shining a light on the ambiguity and uncertainty involved in trust, and homing in on the level of susceptibility and exposure to risk, which leaves the trustor vulnerable. Furthermore, studies also suggest that this condition of vulnerability is exacerbated under closed conditions (when the game is played non-cooperatively), as the establishment of agreements, promises and guarantees is prevented (Riker, 1980, p.10). Clearly acknowledging this moment of vulnerability helps establish a better understanding of why someone may be hesitant to grant their trust. In addition, it establishes the importance of transparency, with hidden information seen to decrease willingness to expose oneself to the risk of trusting.

As a complement to this, consideration of related concepts further illustrates the fundamental role of vulnerability in defining trust. Teasing out the distinctions between reliance and trust exemplifies how trust may go beyond the functional confidence that a task will be completed (Baier, 1986, as cited in Encyclopaedia of Philosophy). Jones echoes this sentiment, explaining that ‘machinery can be relied upon, but only agents, natural or artificial, can be trusted’ (Jones, 1996, p.14, as cited in Encyclopaedia of Philosophy). This suggests that trust should be interpreted as confidence in the good will of the agent to not betray us, and thus we can come to depend on them as reliable guarantors of the promises they make. In the domain of statistics, it is for producers to be trusted, but the statistics themselves to only be relied upon.

Faulkner’s (2018, p.11, as cited in Encyclopaedia of Philosophy) distinction between affective and predictive trust may be helpful here. He proposes that predictive trust is an estimate that one can fulfil the responsibility entrusted to them, whereas affective trust (the emotional and intimate variant) is a thick concept imbued with normativity. In other words, this suggests that affective trust is inherently value-laden (carries positive connotations) and that one ought to be trustworthy (because doing so holds positive value in and of itself). This variant of trust is sympathetic to the notion that to trust someone is to be confident in the assessment that they will not betray you and abuse the vulnerability you have shown. Consequently, it is likely that when experiencing misplaced trust under these conditions, one may feel a strong sense of betrayal. Interestingly, Faulkner does not expect this betrayal to be mirrored in cases of predictive trust. This points to the idea of there being different types of trust, with the implication that actions done to improve trust may not be universally effective, and a bespoke approach is best.

Moreover, although trust may have a reciprocal quality, the burden of trust, and the vulnerability this entails, should not fall exclusively on the public. This is especially important as, even if trust does function as a “reciprocal spiral”, the spiral will never get that initial spark, let alone generate the momentum to sustain the virtuous cycle, if actors do not take the time to acknowledge the true vulnerability involved in the initial moment of trust. This caveat is raised to temper the perception that the recommendations this report proposes are assigned as quick fixes.

That being said, as a recommendation, it may be beneficial for the wider statistical community to display a willingness to take on some of the vulnerability embedded in relationships of trust. This would involve endorsing a mutual approach to trust and producers taking concerted steps to signal their trust in the public. Specific actions include being open and honest about the limitations and confines of statistical outputs and communicating this to the public in an open and transparent manner. Public engagement and outreach projects could be useful spaces to communicate vulnerability.

1.4 Related Concepts: What is Trust Not?

As the above discussion has exemplified, across the disciplines, trust has been defined as an innate personality trait; a reciprocal process; a socially desirable characteristic; and a state of vulnerability. Having outlined these definitions and made positive steps towards understanding what trust is, it important to complete the definitional exercise and explain what trust is not. This is essential to avoid conflating related, but distinct, terms. Furthermore, it provides the structure to ensure that, in talking about increasing trust, recommendations are targeted appropriately.

1.4.1 The Absence of Distrust or Mistrust

The first conflation to disentangle is that trust should not be conceptualised as the absence of distrust or mistrust. These three concepts – trust, mistrust and distrust –are related yet distinct.

As Verhoest et al. (2024) explain, within the literature of trust dynamics there are three core perspectives on how trust and distrust are related:

- Trust and distrust are positioned on opposite ends of a continuum. According to this account, the level of trust afforded to any actor falls somewhere along this spectrum, and at some point on this spectrum, trust switches to distrust. In line with this outlook, levels of trust are responsive and can move between the two extremes, with declining levels of trust eventually contributing to distrust (Citrin & Stoker, 2018).

- Trust and distrust are polar opposites, with neutral ground in between. This perspective conceptualises trust and distrust as rival counterparts whilst also recognising instances where neither trust nor distrust is at the level to constitute, or qualify, as either.

- Finally, trust and distrust are related yet distinct concepts. This perspective views trust and distrust as separate entities, providing the conceptual toolkit to detach the two and move away from this fixed view of trust as a spectrum, or trust and distrust as two opposing extremes.

The principal value of the final approach is it that it avoids falling into the trap of conflating low levels of trust with high levels of distrust. Similarly, it does not consider low levels of distrust to be an appropriate proxy for heightened trust. The observation that low trust and distrust are qualitatively distinct is highlighted in Korsgaard’s review dedicated to reciprocal trust, wherein low trust is identified as a ‘lack of confidence’, whereas distrust implicates ‘negative expectations’. Continuing this distinction, Korsgaard proposes that the two manifest in different behaviours: ‘trust motivates approach behaviour – a willingness to engage and take risks – distrust motivates avoidant behaviour’ (2018, p.14).

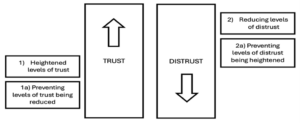

This conscious untangling of these two distinct concepts allows research, understanding and consequently strategies and recommendations to be tailored to the appropriate measure of either: 1) heightening levels of trust; or 2) reducing levels of distrust. Within these two overarching objectives, the supplementary ambitions, 1a) preventing levels of trust being reduced; and 2a) preventing levels of distrust being heightened, come together like so:

An important point to clarify is that mistrust and distrust are not synonyms. While scholars do speak of a ‘family, with trust, mistrust and distrust as members’ (Bunting et al., 2021, p.1), mistrust is analytically different. Distrust refers to a state of ‘cynicism, political disaffection and alienation’ (Citrin & Stoker, 2018, p.50). Meanwhile, linguistically, mistrust is understood to refer to a sense of doubt, suspicion and general unease towards an actor or piece of information. In other words, it describes the use of one’s critical faculties to identify situations where trust is not earned and should be withdrawn. Mistrust can be a response to an actor’s maleficent behaviour or cases where information is found to be inaccurate, intentionally misleading or deliberately misused. Mistrust, specifically political mistrust, is an important part of representative democracies, supporting accountability and critical engagement (van der Meer & Zmerli, 2017, p.1).

The difference is further reiterated by PytlikZillig and Kimbrough (2016), who argue that mistrust reflects initial doubt about whether presented information or an entity is deserving of trust, whereas distrust refers to a situation where the actor is confident in their assessment. One inference of this distinction is that it implies that mistrust is not an outcome, but an important process undertaken in order to help one in their assessment and determine the binary outcome of trust or distrust.

This could be considered to be a positive asset from the perspective of trust building because it is possible that blunders in one’s trust record (such as surrendering blind trust, mistakenly granting trust and/or experiencing betrayals of trust in the past) may contribute towards scepticism and eventually culminate in cynicism and distrust. Consequently – because mistrust is the process of checking and safeguarding against these errors – it is important that it is not dismissed or bypassed. Instead, because mistrust encourages a hesitant and cautious approach, it should be supported and encouraged as part of the critical engagement process.

As a result of this process, it is likely that if the trustor is not confident to take on the risk and has not been reassured of the trustworthiness of the information or entity, they will reach the conclusion (outcome) of distrust. However, if they are confident that the checks have been completed to a satisfactory standard, they are likely to arrive at the outcome of trust. The appearance of mistrust, according to this conceptualisation, is just an extended process of indecision, where the trustor takes the time they need to feel confident arriving at an outcome.

This conceptualisation of mistrust as a process, rather than a middle ground, or part-way progression towards two extremes, supports the conclusion that mistrust is a healthy part of the evaluative process.

Consequently, anyone interested in building trust should not be trying to suppress mistrust. Instead, moments of doubt (which are characteristic of this process) should be viewed as opportunities to exemplify trustworthiness to the audience, and support them in arriving at a confident, and appropriate, assessment.

1.4.2 Trustworthiness

The final concept discussed here, trustworthiness, may seem misplaced in a section titled “What is Trust Not”, especially as this review has made frequent references to trustworthiness both as a feature of trust and a recommendation to improve trust levels. To be clear, the deliberate repositioning of trustworthiness into this section does not contradict nor undermine any of the previous statements: it remains the case that exemplifying trustworthiness is conducive to increased trust. The purpose of the separation is to reiterate that trust and trustworthiness are not synonyms; they are companions.

The distinction between trust and trustworthiness is based on the premise that trust is the outcome, and trustworthiness is an assessment one undertakes in order to determine whether or not someone is “worthy” of our trust. To unpack this further, trust is the object, while trustworthiness is the behaviour. In this regard, rather than demanding trust, one should behave in such a way that trust is willingly given.

This description is what Onora O’Neill refers to as “intelligent trust”, by which she means that trust should only be assigned to those who are trustworthy. In other words, assessing whether someone/something is worthy of trust requires engagement and critical evaluation – trust should not be gifted as a default. To quote her TED talk (2013) once again, ‘The aim to have more trust is a stupid aim. We should aim to have more trust in the trustworthy, and less in those who are not trustworthy.’ This short reflection showcases the lexical difference and echoes the importance of supporting healthy levels of mistrust.

The repositioning of trust as adjacent to trustworthiness is also helpful as it defines trust as a positive asset (which is either socially or normatively desirable) that is earned by repeatedly displaying behaviours one would consider to be worthy of trust. This distinction, in line with Onora O’Neill’s thinking, takes the onus away from the public (the trustor) and places it on the agent who is hoping to be trusted. This distinction avoids assigning blame to the public for their current levels of trust, and places the onus on the agent, prescribing behavioural changes on their part. This is beneficial, as it assigns agency to producers, placing the solution in their hands and suggesting that constructive recommendations for exemplifying trustworthiness can be fruitful.

This reimagining of trust and trustworthiness raises the question: how does one go about determining what behaviours are trustworthy? (as these are the behaviours which will be needed to build trust). In response, the Code of Practice for Statistics provides some initial indicators of how producers can exemplify trust, with the “Trustworthiness” core principle illustrating the most innate, or explicit, synergy.

In this respect, principles such as transparency, impartiality and integrity align with this theme. In addition, active and direct engagement with users, and the use of plain language in statistical bulletins and accompanying documentation, can also contribute to the perception that the producer has nothing to hide, and the statistic has been produced in an honest and competent manner.

The importance of communication is addressed in section 2.2.1, and evidence to support the importance of competency and transparency is provided in section 2.1.3.

Although the alignment between trust and the core principle of Trustworthiness is perhaps the most obvious, the other principles covered in the Code also contain helpful standards.

If adhered to, these standards can either have a positive influence on trust or alternatively provide a safeguard to protect against the deterioration of trust. Ensuring that statistical outputs are of a high quality and fit for user purpose are two such examples.

Their respective impact on trust are addressed in the sections Trust in Evidence, and Trust in Official Statistics, respectively. To quote Radermacher, ‘it is about high-quality information that is well worth trusting’ (2020, p.V).

Back to top