Director General, Ed Humpherson, recently gave the keynote speech at the ISI World Statistics Conference about how official statistics producers need to embrace vulnerability in a time of crisis. Watch the full keynote speech, or read the transcript below.

“Those of you who have been sitting here for a while and looking at the stage might have noticed that I’ve brought something with me, or a pair of things with me, in fact. You might think of them perhaps as being a prop for my talk, or perhaps you might think of them as being a gimmick. What I’d really like you to think of them, though, is perhaps a symbol, a token, a representation of openness, and a vulnerability. Or even think of them as a gesture by me as your speaker this morning to be open enough to leave a pair of my shoes on the table.

Because that’s what I’m going to talk about today. I’m going to talk about openness and vulnerability and how central they are to you, to us, and our identity as people who care about statistics. That’s my main point. I’m going to unpack it through the lens of various ways of looking at the world – various lenses – but talking about other things as well.

I’ve been struck, and I’m sure many of you as well have over the course of this week, in amongst all the great positivity about developments that statisticians around the world are putting into place, a kind of an anxiety. An anxiety that we live in times which are difficult for people who work in official statistics. I won’t enumerate all of the examples that might lead us to that conclusion, but you will have heard people talk about the threat of misinformation, political manipulation and political interference, quality challenges.

And it has struck me that people here from an official statistics background might themselves be feeling vulnerable in the face of this poly-crisis, this multiple series of crises. What I want to persuade you of is that actually we should not let any crisis go to waste, and here is an opportunity for people who produce official statistics to demonstrate our secret sauce. Our secret sauce is openness and vulnerability. That’s the point of this talk.

But I’m going to begin somewhere else. I’m going to begin on the streets of the town I live in, Kingston upon Thames in South London. About four weeks ago, I was walking along near my house and I saw these shoes on a little wall outside somebody’s house, I thought looking quite forlorn, in fact, a rather sad pair of shoes on their own. And my first thought was that somebody had lost them, and they had been placed there in case the parent came back to pick them, pick them up. But then I realised that as I looked around, there were other examples in nearby streets of people leaving things out outside their house. And what they’re doing is, they’re leaving things outside their house for other people to collect.

So here are three examples – there are people who say, I’ve got some stuff in my house, I don’t need it, but somebody might. So I don’t know if you can see, but there’s a box here, it says ‘free’ it’s a very sort of casually presented box, but it’s got some stuff in it people might like. And here, a little basket of scarves. Somebody’s obviously getting rid of their scarves. Somebody might like them. It’s a phenomenon of free exchange. And one of my thoughts about this has been, a few years ago, I don’t think I saw this very much. I don’t think I saw people putting things outside on the walls of their house, from outside their house, for other people to take.

You also see this phenomenon on the internet – free-exchange websites where people put things for other people to take. I thought that was interesting. But I put that thought away and went back to my day job. And then I started to realise there was something connected to our work, which I’ll come on to.

But what I want to say today is this: I will start with the evolving nature of trust. Then I want to talk about official statistics serving the public good, and then my organisation’s role, and then I want to talk about the crises and how we’ve responded, and I want to close by really driving home this point about vulnerability.

The evolving nature of trust

The evolving nature of trust. I’ve been reading a lot about trust recently. The literature has revolved around a paper written in 1995 by an American academic called Mayer. In Mayer’s model of trust, he says: for person A to trust organisation B, they need to perceive that organisation B has competence, integrity and benevolence. So that’s the standard. It’s called the CIB model: competence, integrity, benevolence. What’s interesting is how understanding of trust has evolved.

More recently, sociologists and psychologists who’ve looked into this say that over time, of those three, benevolence is becoming more important. That instead of trusting somebody because of their competence, or their integrity, you most need to trust that they are benevolent towards you. That they share your interests and they act in your interests.

The second element of this evolution is the observation that trust is shifting from being something which people look upwards to institutions to provide – the state, the church, a charity perhaps, into something which is more relational, more horizontal, more equal. It’s to do with interpersonal relations of shared equality, not of hierarchy. So these are two ways of thinking about trust. One is a shift away from just competence and integrity towards benevolence being more important. And the second is this shift from institutional and vertical to horizontal and relational.

The ‘shoes outside the house’ is an illustration of that, because I’m pretty certain that 15 years ago, the same people would’ve given their unwanted things to a church or to a charity to sell. They’d have gone upwards to an institution, whereas now they’re bypassing, disintermediating the institution. I also think it’s quite a vulnerable thing to do. There’s some vulnerability about putting something personal of yours out for everybody to see. So that’s the evolving nature of trust that’s going to come back in this talk in a few minutes.

Official statistics and the public good

Hold that thought while I just say a little bit about official statistics and the public good. And I have to make an apology here. The more I’ve been here this week and heard other people talk – I’ve heard Walter Radermacher say this, I’ve heard Steve McFeely say this – that maybe there’s something about the term ‘official statistics’ that isn’t quite right, that maybe that sounds too austere and too distant, too remote. And maybe we should talk about public statistics. And in the UK, the Royal Statistical Society has done a very nice body of work promoting the idea of public statistics. And I hope that in future years, if I was to do a talk again, that’s what I’d say. I’m using the term official statistics now because that’s a term that we commonly use. But just to say, I acknowledge the limitations of the term official statistics.

Anyway, official statistics should serve the public good. This is the definition we use in the UK. I won’t read it out, but it emphasises that they are public assets.

Statistics serve the public good as public assets that provide insight, which allows them to be used widely for informing understanding and shaping action.

To fully realise the potential of statistics, the organisations producing them should place serving the public good at the heart of their work and be conscious of their responsibilities to society.

They are for the public. They’re about the public, and that is what enables them to be used widely for informing, understanding. And moreover, my organisation – which I’ll explain in a second what we do – we believe that to fully realise the potential, organisations, NSOs, official statistics producers must place the public good at the heart of their work. That is essential.

In my view many official statistics producers convey their authority as if they’re a central bank. This is a photograph of the Bank of England. It’s a very powerful, robust facade. It emphasises its national nature, there’s a flag flying on top, it’s got strong pillars. Everything about it is conveying solidity and reliability, and confidence. It’s all competence and integrity. I think official statistics producers often convey to their societies their role, their authority, in this way. They say: We have very strong methods, we have very strong data ethics, we have tremendous frameworks for statistical disclosure control. We have competence, we have integrity. What I worry about is, if I’m right that the nature of trust is shifting, then competence and integrity aren’t enough.

The far strong facade of the Bank of England, the strong facade of an NSO, does not convey warmth or benevolence. It does not convey relationship. And I think that could be a growing challenge. Lots of the things which have happened in different ways around statistics might have something to do with this, as well as the more obvious causes. So I think benevolence and openness are really very important.

The Office for Statistics Regulation

So, what’s my organisation? We’re rather unusual in the global official statistics community. Not unique – as I’ve learned very well this week from Martine Durand at the French Statistics Authority, which does very similar work to us, but we’re certainly unusual.

We are a separate body and we are responsible for setting the UK’s Code of Practice for reviewing compliance with that Code of Practice. And when we review compliance, I mean, we really review it because if we find statistics that are not compliant, we remove their accreditation as official statistics, which is quite a strong intervention. We act as a catalyst for systemic improvements. We do reports on things like data sharing or on cross-UK comparability so that a user could compare statistics in Scotland with those in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Perhaps what we may be most known for is that we are willing to stand up for the use of statistics – the appropriate use of statistics in the public domain. What that means is that we will sometimes make public statements about the ways in which statistics may be being misinterpreted or being misleading for the public. I think that’s maybe relatively unusual in the world of official statistics. But if you believe everything that I’ve said already, you can see how important it is to serve the public in this way.

So that’s what we do. Everything we do is built around three lenses on statistics which we call TQV: Trustworthiness, Quality and Value. Trustworthiness is about the organisation that does the producing, and I suppose this is closest to the competence and integrity part of trust. It’s about the organisation’s practices, its commitments, the ways in which it manages itself. Quality is about the data, how data are collected, how then they’re converted into aggregate statistics, the strengths and limitations, the uncertainties that surround those statistics. Value is about what the statistics mean for users in society.

So we always use this framework. Everything we look at will have a T and a Q and a V component. We think looking at any one of those in isolation will tend to only give a partial picture. So that’s TQV.

For today’s purposes, what’s so interesting about TQV is it’s really all about openness. Trustworthiness is all about being open to recognise your errors. If you find an error as a statistics producer, you don’t hide it away and think that’s embarrassing. You notify your users promptly, openly, clearly, because that is you doing your job. You always recognise the limitations and imperfections of the statistics that you produce. And you should not do that just in a very technical way, presenting your confidence intervals, for example. You do that in a way that helps a user know what they should or should not infer from the statistics. Openness to uncertainty, understanding, conveying that statistics are always an imperfect measure of what they’re trying to capture. Being honest and clear about that uncertainty. Openness to users, always having an open door to understand what users want, how they use statistics. And finally, and I think this is probably underplayed often, it’s openness to dialogue. People will challenge the statistics that are produced by statistics bodies. They will see a flaw in them. They will say, hang on, I’ve delved into your underlying data, or I’ve looked at your metadata, and something isn’t right here. Welcome that – that is absolutely fantastic. That is your best friend in terms of quality control. Be open to dialogue, debate, different voices and different perspectives. And if you’re open in all of those ways, you will be demonstrating vulnerability. You’ll be opening yourself up. You will metaphorically be putting your shoes on the table, or be putting your shoes on the street. That’s the secret sauce. That’s what TQV is all about.

Three challenges that have faced UK official statistics

So the three challenges that I want to talk about, which I think illustrate these themes in practice. The first is the way in which statistics have become weaponised in political discourse. By weaponised, I mean, instead of statistics providing an insight to a user, they get used in political debate as a way of repeating the same number over and over again, almost until it loses all its meaning as a way of sort of hammering home a simple and often misleading message. That’s the weaponisation of statistics.

Second, we know that we live in a world where users demand real-time or as close to real-time data as they can. That’s a difficult demand for statistics producers to meet.

Third, and very specifically in the UK, I’m going to talk about the challenges which have faced and are facing economic statistics, which Roeland alluded to earlier.

So, weaponisation. I’ve got a picture here of the most famous weaponised statistic in recent British political history. This is to do with the Brexit referendum. There was a statistic pasted on the side of a bus. My organisation, OSR, we got involved in highlighting the ways in which that might be misleading.

For a long time as a result of that experience, I thought that our job was to highlight something which was wrong and say it was wrong, and it was only subsequently that I realised there was a much bigger and more important story around this whole thing, which is in the phrase ‘that’s not my GDP’. For those of you who don’t know it, this is the story, it’s a real story. During the debates around whether Britain should vote to leave the European Union or not, an economist was presenting to a town hall meeting in the north of England and he said, well, one of the things about Brexit is you might want to think about the impact on GDP. And he said, ‘GDP has been rising, maybe we don’t want to endanger that’. And a lady in the audience put her hand up and said, ‘that’s your bloody GDP, it’s not mine’. And what is meant by that is, that’s kind of a big abstract number. You know, I don’t eat GDP. I don’t clothe my children in GDP. My children’s shoes are not GDP. I want to know about something which is meaningful to me.

I’ve always thought that is such a great way of illustrating the ways in which statistics, when they’re weaponised, can become remote from the people that they’re about. If people say those are not my numbers, I think we’re in trouble. So, over the succession of things I’ve listed there, starting with the UK’s contribution to the European Union, and then claims about educational performance, and then the COVID pandemic, particularly debates around vaccines, and more recently, debates about migration and debates in our 2024 general election. I’ve shifted my view from being it’s our job to highlight what might be called ‘lying scoundrels’. Frankly, I don’t think that anymore. I think it’s our job to represent the people who might not see the numbers being relevant to them. That’s the way to respond to weaponisation of statistics.

Excess demand of real time data

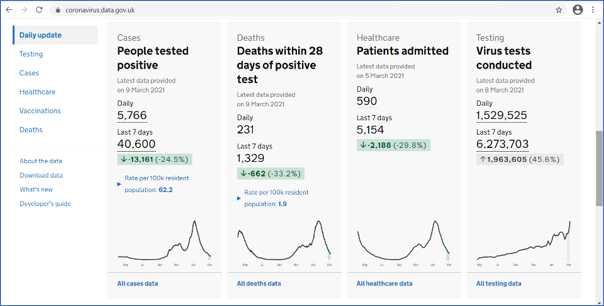

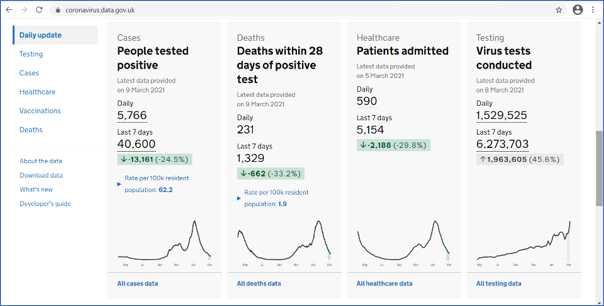

This little screenshot I’ve got here is of a fantastic tool that the UK Department of Health produced, which was a real-time COVID dashboard, updated daily, which gave real-time picture of infections, hospitalisations, deaths and vaccine rollout when vaccines came. You could visit it, you could click down to an incredibly low geographical area. Updated daily. It was incredibly popular. At its peak, it had about 70 million hits a day, which is an astonishing number for a single government website on a single day.

We responded to this. You might say that a statistics regulator would, might, suck our teeth about all of this dirty data going out. You know, where’s the quality assurance on that? But in fact we really supported it. We did some rapid reviews. We allowed them to release it not at the standard time of 9:30, but at 4:00 PM, because that was the time when the daily government press statement came out. We wanted to make sure that the information was available to everybody at the same time. We continually focused on the transparency of government evidence. And, we said, you know, there’s a code of practice, which we obviously love, but the most important thing are the principles of the Code. And as long as the people producing this kind of dashboard followed the principles, perhaps the detail of compliance matters less.

The final kind of crisis is the one which is, I guess, upon us now, which is the quality of UK economic statistics. And there are many ways of telling this story. I’m going to focus in on survey response rates, which I guess has been sort of the most proximate public reason that people have become concerned about economic statistics. I have two charts here. The upper one shows that the UK has always been towards the bottom end of response rates for Labour Force Survey statistics. The UK is the heavy black line; the other lines are other European countries. The lower chart is a different survey, the Living Cost and Food Survey, showing – because it’s too small, you won’t be able to see the time period, but really, in the period more recently after the pandemic – a really significant drop off in the response rates to that survey, rendering it increasingly unrepresentative. That’s the problem: the lack of representativeness.

Our response to this process of declining quality is a different kind of openness. Maybe it’s a painful kind of openness. It’s the openness which says, these statistics are no longer as reliable as they were. As a result, we have removed the official statistics designation from several statistics produced by the Office for National Statistics. I’ve listed them there. We also did a thematic review looking at economic statistics in full earlier this year, which said: there are really significant problems, and the first step for ONS to get its head around these problems is for ONS to fully recognise them as problems and then set out plans to respond to them. It’s no good just to say, don’t worry, we’ve got a plan, nothing to see here. Open up and say there are real problems. And the great news is the ONS has done that. That’s my bottom box here. There’s an excellent recovery plan now, which fully recognises the issues, and is showing the openness which has been the theme of my whole talk.

So what have I learned from these challenges? In a sense, what’s my vulnerability that I can share with you? The first is I made a mistake earlier on in doing this job. I thought we were campaigners to defend the truth. I no longer think that. I don’t think that’s the right way to think about statistics, because it sort of puts statistics on a pedestal they can’t possibly ever sustain. What we are is we’re advocates of a kind of transparency in the use of statistics that enables an intelligent user to understand what they mean. That’s what we do. When we make an intervention, when we write to a minister, when we make a statement in the media, that’s what we’re doing. Intelligent transparency. It’s not this sort of fact-checking, truth-correction role. I’ve learned that.

The second thing I’ve learned is that in times of high demand, an organisation like mine can be a real pain in the ass. We can say, you know, you need to do things in the right way and in the right order. And I think it’s really essential that we demonstrate flexibility, that we support producers in their responses. And then the third thing is, I talked about the succession of problems with economic statistics. I honestly think we could have highlighted the problems more clearly. I think everything that has happened, we said, you know, we picked it out as a problem. I’m not sure if we did it quite loudly enough. And that, that is one of my reflections and one of the things I say in the mirror in the morning is maybe I could have done a better job there.

The key point though, through all of this is, I think what I’m trying to get across is that the technocratic distance of being ‘we are the official statistics body, we have the best statistics’. That won’t help any of you who are OS producers. What will help is openness and vulnerability.

Openness and vulnerability in practice

So I just want to have my final section to say what I think that means in practice. The first thing I think it means is, you should be on the front line, you should be out there, you should be engaging with users. There are actually some great examples that the ONS in the UK is doing to encourage citizens to respond, to see if response rates can be increased by direct and appealing engagements. The two screenshots I’ve got are of two approaches. ‘It starts with you’, is the tagline. I think it’s rather nice and although I’m not sure whether the evidence is fully in, I understand that the early signs are, it really does help. So the lesson is: be on the frontline, engage, go out there and engage. Whilst doing that, recognise, although I’ve used the word public, of course, that’s a really silly thing to say. There’s not a public; there are multiple publics. There are different people in different places, in different communities who have different interests.

And just to illustrate that, we produced a piece of work, my organisation, earlier this year called ‘Statistics in Personal Decision Making’, where we went out to both a survey panel, but also some focus groups, and asked people, individuals, how they use statistics in their daily life. And it was completely fascinating. The answer is sometimes not at all, and sometimes much more than you’d expect. But that kind of insight of saying there’s a public out there, which is not really very well served by our current notion of users being sort of experts, is really important. So recognising not a single public.

And then three things to avoid. Avoid distance. If you’re in an OS producer and you ever think like, well, we’re conveying ourselves as this authoritative, ‘best producer of statistics that there are, you can trust us because we have all of this competence’. Well, you’re probably going down the wrong path. Associated with that is don’t ever fall into the trap of thinking the statistics you produce are perfect, that they’re a perfect single point. I always get really worried when ONS will publish a statistic and some expert user will say, I think it’s flawed here. And the ONS response can sometimes be ‘this is the best available estimate, or this is using the best available methods’. I always think that’s so dismissive. Don’t find yourself saying that. It’s a mistake.

And the final one. I always wanted to be the last person in the world to have an AI component to my talks because I don’t know anything about it, basically. But then I realised I can’t really do that – we’re in the world where everybody has to talk about AI. So this is my little nod to there being an AI thing out there.

I think there’s a tendency in the data and the AI world to regard data as a block of stuff that you shovel in. And I love this image of a man shovelling coal into a steam engine. It summarises the way AI is conceptualised. I believe there’s a tendency in the big data and the AI world to think of statistics being just another thing that you shovel in and then some magic happens inside the furnace. I think we should be really wary of that, because of course, we all know that the richness comes from the insight, from the metadata, from the limitations as much as from the strengths.

So that’s my attempt to say something about AI! I don’t think it’s very convincing, but I thought I better put it in because everybody talks about AI in their presentations these days.

Conclusion

So here is my conclusion.

If trust is shifting from institutional to relational,

and the key to trust is now benevolence,

then official statistics producers need to avoid technocratic distance

and instead they must demonstrate openness and vulnerability.

That’s my argument. And just to put it another way, visually: if you find yourself thinking like a central bank, all pillars and solidity: don’t. Don’t think like that. Instead, think of this: the shoes in the street.

Thank you.”