Results and Discussion

Quantitative Results - Stage One: Which public benefits are referred to most frequently in NSDEC and RAP applications

Most frequently mentioned

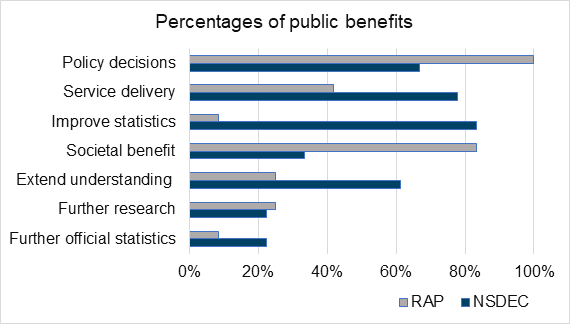

The quantitative analysis demonstrated some patterns in which public benefits were mentioned most frequently. As can be seen in Figure 1[1], the most frequently mentioned public benefit delivered by NSDEC applications was improve statistics (15 mentions), followed by service delivery (14 mentions). In the RAP applications, the most frequently mentioned public benefits were policy decisions (12 mentions) and societal benefit (10 mentions).

[1] Please note that the percentage indicates the proportion of applicants who referred to each public benefit. This could be up to 100% in each column as applicants could refer to as many as seven benefits in their applications.

Back to topFigure 1: Percentage of public benefits included in applications

Back to top

Back to topThe data in Figure 1 can be found in an accessible format in Table 4.

Out of the four most frequently mentioned public benefits, three of them focused on providing evidence related to policy. This may imply that a majority of researchers applying to the NSDEC or the RAP feel that this is the most important benefit that their research can deliver. However, as researchers are not being explicitly asked for their views on public benefits, it could also be argued that researchers believe that referring to policy in their applications may demonstrate the impact of their work, as well as increasing their chances of gaining approval from the data owner. Improve statistics was also one of the most frequently mentioned public benefits but, unlike the three discussed, it does not relate to policy; this will be discussed in the section below.

Least frequently mentioned

In terms of considering which public benefits are not frequently mentioned, in the NSDEC the two least frequently mentioned public benefits were to further official statistics and further research, with four mentions each. It is not clear why these public benefits were mentioned least but perhaps it could be that applicants do not feel that furthering research or official statistics as a public benefit is their responsibility, as these public benefits may be served by statistics producers.

In the RAP applications, the least frequently mentioned public benefits were to further official statistics (one mention) and to improve statistics (one mention). However, in contrast, improve statistics was the most frequently mentioned public benefit in the NSDEC applications. This begs the question of why there is such a great difference between improve statistics and further official statistics being referred to in the NSDEC applications, especially as they are mentioned equally infrequently in the RAP applications.

Examining the wording of these public benefits more closely, (Improve statistics: To improve the quality, coverage or presentation of existing statistical information or Further official statistics: To replicate, validate or challenge Official Statistics), it could be argued that one of the main differences is the reference to statistics being ‘official’. If researchers in the NSDEC are unclear about the distinction between ‘official statistics’ and statistics (or the distinction between these types of public good), they may be less likely to refer to official statistics in their application.

A further difference is that further official statistics refers to challenging existing statistics; it could be speculated that researchers are reluctant to explicitly say that they intend to challenge official statistics in case this is looked upon unfavourably. Interviewing previous applicants and potential applicants to the NSDEC and RAP may provide useful insights to explain why this pattern exists and would develop our understanding of how these categories are viewed and interpreted.

Further Observations

One category which has not yet been referenced is to extend understanding. This category refers more explicitly to the SRSA definition of the public good and it is probably the most direct route for research to benefit the public. The Research Code of Practice and Accreditation Criteria states that research and its results must be transparent, and the NSDEC’s ethical principles mean that researchers must consider the views of the public in light of the data used, suggesting that research findings should be made available to the public. Arguably, any research which is publicly available has the potential to extend understanding but this category was mentioned by 50% of the applications.

Perhaps the reason for this relates to it being less of a priority for researchers, or perhaps researchers are unsure what findings the public may consider interesting. A follow-up dialogue with the public exploring their attitudes to published research, and the public benefits it might create, may be useful in understanding this point and whether some topics of research are seen as more relevant to the public good than others.

Additionally, looking more closely at the wording of this public benefit in full, it includes the phrase ‘challenging widely accepted analyses’. It could be that, as we argued in the last section, researchers are uncomfortable explicitly stating in their applications that they will challenge current analyses in case this is perceived negatively. Again, dialogues with researchers about their perceptions of these categories of public benefits may provide useful insights into whether this is the case.

Back to topStage Two: How do the NSDEC and RAP applications compare with each other?

The findings (illustrated in Table 4) demonstrate that the greatest difference (75%) in mentions of public benefits between the two applications was to improve statistics such that 83% of applications to the NSDEC mentioned it compared to 8% of RAP applications.

Table 4: The number and percentage of public benefits in the applications

| Policy decisions | Service delivery | Societal benefit | Further official statistics | Further research | Improve statistics | Extend understanding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSDEC | 12 (67%) | 14 (78%) | 6 (33%) | 4 (22%) | 4 (22%) | 15 (83%) | 11 (61%) |

| RAP | 12 (100%) | 5 (42%) | 10 (83%) | 1 (8%) | 3 (25%) | 1 (8%) | 3 (25%) |

| Difference in percent | 33% | 36% | 50% | 14% | 3% | 75% | 36% |

The next greatest difference (50%) was in societal benefit, as 83% of RAP applications mentioned this compared to 33% of NSDEC applications. There was also a 36% difference in mentions of extend understanding as this was mentioned more frequently in NSDEC applications (61%) compared to RAP applications (25%).

These differences may be explained in terms of the types of applicants applying to each process. There are more academics applying to the RAP and very few applying to the NSDEC, most likely due to the fact that applicants affiliated with universities usually have access to ethical approval processes within their institutions. Applications to the NSDEC therefore tended to come from government employees or organisations. These patterns are echoed in the sampling of applications[4] and the differences in Table 4 may reflect how the types of applicants differ in terms of their priorities and responsibilities.

Are there patterns in how often public benefits are referred to comparing types of applicant or themes of research?

As can be seen in the Appendix[5] (Table 6), applications from the Government were more likely to cite that their research will improve statistics. By contrast, both organisations and academics applying to the NSDEC and RAP more often cited that their research would contribute towards improving the evidence base for policy decisions. Academics (who mainly applied to the RAP) may aim to provide an evidence base for policy decisions in order to create impact in their work. This may be a particular priority for academics participating in the Research Excellence Framework where impact beyond academia is assessed. Further, perhaps government employees feel that improving statistics is more of a priority for them in serving the public good.

In terms of considering the public benefits referred to across research themes (see Table 7), three of the themes (children, business, and population) referred to policy decisions most frequently whereas health research referred to societal benefit and service delivery most frequently. Conclusions could not be drawn about the final theme (environment) as the public benefits associated with these applications were spread across multiple categories. It is also noteworthy that the environment theme had the smallest number of applications associated with it, which could imply that there is less available data to analyse on this topic or fewer researchers interested in exploring this data.

[4] Applications from academia: RAP=50, NSDEC=3; a government department RAP=11, NSDEC=27; or other organisations (private sector businesses or third sector organisations) RAP=29, NSDEC=20.

[5] It is important to note the small numbers of applications when we examine them in this more granular way.

Back to top

Qualitative Results

We carried out a qualitative analysis on the applications to determine if there were other identifiable themes which could provide further insights into how researchers describe the public good in their applications. Again, our focus was on the section of the applications which related to public good which were examined in the quantitative analysis.

One point of interest was how much public good or public benefit were explicitly discussed. In the RAP applications, public good or public benefits are never referred to (perhaps due to the layout of the application) and in the NSDEC applications, public benefit was referred to by 6 applications out of 18 but there was no consistent pattern to these mentions which elaborated on the conceptualisation of the term.

Are other public benefits referred to in the applications?

The analysis showed that one benefit referred to was public spending. Public spending may relate to societal benefit or policy decisions but words such as cost, value for money, prioritising spending and funding were explicitly mentioned in 14 out of 30 applications. This may suggest that some applicants view saving public money, or using public money more effectively, as a public good which the RAP, the NSDEC, or the original statistics producers within the government will respond positively to.

Example from the texts are provided below and all identifying information has been removed.

A further observation which is apparent in a number of applications is how often regional information is referred to. Six out of thirty applications referred to improving regional information, for example:

This reference to regionality may refer to the improvement of statistics category because it will lead to increased granularity. However, this specific use of data could also be described as increasing equality of access or representation in data, which may be another way of conceptualising the public good.

A further public good which was described in some applications was data linkage, for example:

These applications identify the important contribution that data linkage can have towards the public good. Further, some applications also refer to how their research will facilitate collaborative working, as one highlights:

These researchers are attempting to move away from working practices which could encourage ‘silos’ of researchers, each working in isolation, which can lead to duplicated effort and wasted resources. The facilitation of collaborative research was also referred to by two other applications. These findings suggest that collaborative research and data linkage are viewed as public benefits by these applicants.

Further insights

One observation which applies particularly to the NSDEC applications is how much time is spent providing background information about the project which does not pertain to the public good or any public benefits. Seven of the NSDEC applications contained at least one paragraph which had no clear reference to the benefits of the research but instead provided extraneous or historical information. There is no minimum word count in this part of the application, and there is guidance available for researchers completing the applications, so it is unclear why information like this has been included in the applications.

Back to top

Limitations and future research

It is important to note that the current study is based on applications to access data which may not mean it is truly representative of how researchers personally define or conceptualise public good. Applications may also reflect what the applicant believes the committee, the panel, or the data owner, may be looking for in the application. Furthermore, guidance is provided to applicants on how to complete the applications, which may influence the way they consider the public good. It is also the case that the applications have probably been through a series of revisions before publication, meaning that other people may have had the opportunity to shape the application. It would be advisable for further research to explore this topic more thoroughly with researchers directly, in an interview or focus group format, in order to canvas their personal interpretation of the public good.

A further limitation to note is that the applications were sampled to be representative but, due to the small numbers of applications which referred to the environment, it was not possible to include environment themed RAP applications.

This research project could be carried out again in the future as the number of applicants to the NSDEC and the RAP will have increased, allowing sampling to become more representative. This could also allow for an inferential analysis of all the applications to take place and potential use of software which could automatically code the applications to allow for a more in-depth analysis.

Back to top