Chapter 3: Do people use official statistics to make personal decisions?

Chapter summary and implications

In this chapter, we present findings from respondents’ answers to questions both from previous surveys and our own, as well as qualitative interviews, suggesting that a substantial proportion of the UK public uses official statistics to inform personal decisions. However, the analysis highlights limitations in the use of surveys to capture this information, with results varying markedly depending on the specific wording and answer options provided. Across the two existing survey questions we reviewed alongside our own new question, the proportion of respondents reporting that they used statistics to make decisions ranged from 35% to over 50%, emphasising the need for caution when interpreting precise figures or tracking changes over time.

These findings also serve as a general reminder to those working with statistics, especially in communicating them to the public, not to assume a uniform understanding of terms like “statistics” or “official statistics”. This observation aligns with previous research, such as OSR’s public dialogue study, which found that words like “research” and “data” can mean different things to different people depending on their personal experiences and knowledge.

Some of our findings also indicate that research, in particular surveys, may even underestimate actual engagement with official statistics for personal decision-making. For instance, providing three concrete examples of official statistics seemed to increase the likelihood of respondents recognising that they had previously used data from official statistics in decision-making, suggesting that engagement levels might have been even higher if more-concrete examples were provided. Similarly, we also found that interview participants were not always aware that they had used data from official statistics for personal decision-making, particularly when accessing them through intermediaries. This suggests that indirect interactions with official statistics may be more common than participants explicitly recognise.

Finally, similar to evidence from other surveys, we found demographic differences, with male participants, younger participants and those with higher education and in higher socioeconomic groups reporting higher use of official statistics for personal decision-making.

Back to top3.1. Evidence from the Public Confidence in Official Statistics survey

The last two waves of the UK Statistics Authority survey on Public Confidence in Official Statistics (PCOS) (Maplethorpe, Popa and Dyer, 2024; Butt, Swannell and Pathania, 2022) asked respondents whether statistics had helped them make a decision about their life in the past month. In the most recent survey conducted in 2023, 40% of respondents who provided an answer agreed with this statement, compared to 52% in the previous wave conducted in 2021. PCOS authors propose that this drop may be linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, which gave additional prominence to official statistics; in 2021, individuals may have relied more heavily on statistics, such as infection and death rates, to guide behavioural decisions about social distancing and other safety measures.

Through our own semi-structured interviews, we explored the underlying cognitive reasoning behind responses to the PCOS question, for example by asking why participants answered the question in the way they did. For the 21 participants who had agreed with the statement during their recruitment to the research, we explored the types of statistics that they had used, and the specific decisions that these statistics had influenced.

Our findings suggest that the PCOS question should not be used to consider how much people use “official statistics”. While participants gave some examples of official statistics, such as crime data (to decide where to move) or school statistics (to choose a school), typically, they thought much more broadly about the term “statistics”. In a few instances, participants themselves recognised that their response depended heavily on how “statistics” is interpreted:

‘I actually ummed and ahhed about that one, because I didn’t know what people would class as statistics. For me, statistics is any data that has come out from a trend, whatever that could be, rather than simple arithmetic stuff.’ (male, 35–44, engineer)

Participants viewed “statistics” as a broad category of information and data involving numbers. The most common example included participants using information about the quality and price of products and services, as well as online reviews, to inform purchases:

‘I do use stats. Even if I am buying something I will look at reviews and I will look at percentages, you know like Trustpilot and stuff. Say I buy something, and I have never heard of the website before, I would always look at the stats and the reviews. I do use that a lot.’ (male, 35–44, consultant)

Other examples included using weather forecasts when deciding what clothes to wear and what activities to do; using smartwatch health data when deciding to seek medical advice; and doing personal budgeting when planning holidays and retirement:

‘I was looking at it personally, my own personal statistics, i.e., pension plans, savings plans, information that I have put together myself in terms of my finances.’ (female, 65+, supervisor)

Another relevant question in the PCOS survey asked respondents whether they had used or referred to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) statistics for any purpose, such as study, work or personal interests. In the most recent survey conducted in 2023, 35% of respondents said they had used or referred to ONS statistics. This was split between respondents reporting that they used ONS statistics frequently (4%), occasionally (24%) or at least 5 years ago (7%).

Back to top3.2. New survey question on using official statistics for decisions

To supplement the PCOS questions, we ran our own survey question focused specifically on official statistics. Respondents were first presented with the following definition of official statistics:

Official statistics are produced on behalf of the UK Government and devolved administrations (governments in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales). They provide information that helps us understand the economy, society and environment. The people producing official statistical follow professional standards and are accountable to an independent regulator. Some examples of official statistics include:

- the level of inflation in the UK

- the amount of crime happening each year

- the quality of air in different parts of the country

After reading this definition, survey respondents were asked if they believed that they had ever used official statistics to help them make a decision. 50% answered “yes”. This figure is higher than the positive responses to the two 2023 PCOS questions, which recorded 40% and 35% of respondents answering “yes”, respectively (see Table 1 below).

The difference may partly or entirely stem from key variations in question design. Our question included a broader time frame (“ever”) than the two PCOS questions. We also included a more detailed introductory paragraph defining official statistics. While this text, like the second PCOS question, noted that official statistics relate to the “economy, society and environment”, we also gave three concrete examples of official statistics: inflation, crime and air quality statistics. These examples likely improved respondents’ understanding of the term “official statistics”, and may have contributed to the higher rate of positive responses.

The impact of providing specific examples alongside the question was evident in the subsequent open-ended survey responses, where respondents described the types of official statistics that they had used and how these had informed their decisions. The most common statistics participants described using were those on crime, house prices, inflation and air quality. Of these, only house price statistics were not explicitly mentioned in the introductory paragraph.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the differences.

| PCOS decision question | PCOS use and reference question | KCL/BIT Our question |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of statistics | statistics | statistics produced by the ONS (with an introductory sentence defining the ONS as an organisation that “produces official statistics on the state of our economy, society, and our environment” | official statistics (with an introductory paragraph providing a definition including examples) |

| Purpose | helped make a decision in personal life | used or referenced, for any purpose, such as study, work or personal interest | helped make a decision |

| Time period | last month | frequently, occasionally, at least 5 years ago | ever |

| Finding in most recent survey | 40% | 35% | 50% |

We also observed differences, by demographic factors, in how our survey sample reported using official statistics for personal decision-making:

- Sex: male respondents reported higher use of official statistics than female respondents (55% vs. 45%).

- Socioeconomic status: respondents in higher socioeconomic groups (A, B, C1) reported higher use than those in in lower socioeconomic groups (C2, D, E) (61% vs. 43%).

- Education: respondents with higher formal education levels reported the highest use (64% for those with degree level or higher, 47% for those with GCSEs, 31% for those with no formal qualifications).

- Age: those in younger age groups reported higher use compared to those in older age groups (from a high of 67% for 18–24-year-olds to a low of 34% for those aged 65 and older).

- Data experience: respondents who had experience working in data analysis reported higher use compared to those who had not worked in data analysis (76% vs. 44%).

It should be noted that these are observed differences and have not been tested for significance; however, it is interesting that they are broadly aligned with demographic differences identified in the 2023 PCOS survey. While the PCOS question that explored demographic differences looked at ONS statistics specifically and the exact numbers differ, it was also found that older respondents reported less use of statistics use for personal decision-making, men reported higher use than women, and those with higher education and in higher socioeconomic groups reported higher use.

Back to top3.3. New survey question on information sources used for decisions

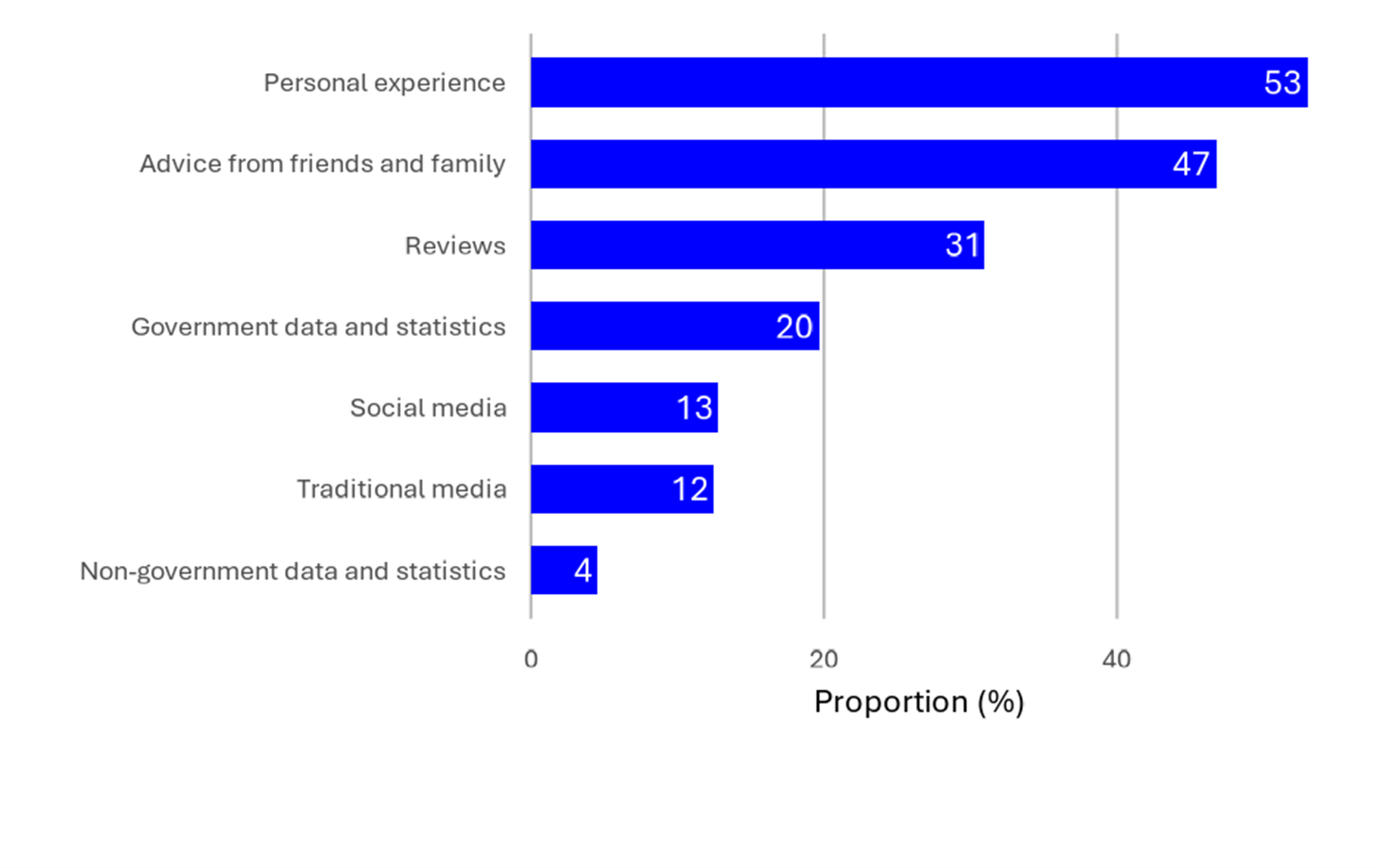

In our survey, all respondents were also asked about the sources that they used to make six different decisions (choosing which primary school to apply to; choosing a GP; choosing where to live; choosing a new job; choosing a baby name; choosing to ask for a pay rise). When averaged across those six decisions, personal experience was the most popular source of information, followed by advice from friends and family and reviews (see Figure 1 below). “Government data and statistics” ranked fourth, with an average of 20% of respondents indicating that they would use them in their decision-making, while 4% indicated that they would use “non-government data and statistics”. For this question, we referred to “government data and statistics” and “non-government data and statistics” to avoid having to define official statistics early in the survey.

Figure 1. Information sources respondents would use to help make six decisions.

Note: Averaged data of which information sources respondents would use to help make six decisions presented to them, including choosing a baby name, choosing which primary school to apply to for your child, choosing where to live, choosing a GP, choosing a new job, and choosing to ask for a pay rise at work. See [info] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Respondents could select multiple options. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

Table 2. Use of data and statistics to help respondents make six decisions

| Decision | Government data and statistics | Non government data and statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing which primary school to apply to | 43% | 15% |

| Choosing a GP | 26% | 9% |

| Choosing where to live | 25% | 13% |

| Choosing to ask for a pay rise | 20% | 12% |

| Choosing a new job | 19% | 14% |

| Choosing a baby name | 13% | 5% |

Note: Respondents who would use data and statistics to help make each of the six decisions presented to them. See question [info] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

Our interviews also provided many examples of official statistics or the data that underpin them indeed being used to inform personal decision-making. For instance, when choosing a primary school, interview participants reported using data on academic performance, attendance rates and pupil diversity. These data were found on council or government websites, including the Department for Education’s school comparison tool. However, the most commonly referenced source was school inspection reports and ratings, such as those from the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted).

Similarly, when deciding where to live, interview participants reported using data from official police recorded crime statistics to assess the safety of local areas. They explained that in some cases, these statistics influenced their decisions, as was the case for this survey respondent:

‘The area I live in was low crime according to official stats, which help make my decision to move here.’ (survey respondent)

Back to top3.4. Finding and using statistics through intermediaries

During interviews, we found that participants who had used official statistics or data from them were often unaware of it, as they accessed the data indirectly through non-official websites and intermediaries. Participants primarily relied on Google searches to find information for personal decision-making, rarely seeking official statistical specifically or deliberately. However, they did come across them, sometimes without realising it. Google searches often directed participants to non-official websites and intermediaries that used official statistics.

While intermediaries are often associated with traditional and social media (see Runge et al. 2022), this research revealed a broader range of sources. Examples included property websites like Zoopla and Rightmove, which linked to government data about crime and schools (albeit not official statistics themselves); baby websites that featured official statistics on popular baby names; and school websites that provided official school performance statistics.

The baby name statistics are a particularly good example of how respondents may have stumbled across and used official statistics unknowingly. Survey respondents reported very little use of government data and statistics for helping to choose a baby name. In fact, both interview participants and survey respondents, in open-ended responses, said that the decision was perceived to be a deeply personal and emotional one, and so unsuitable for official statistics. One respondent said that naming a baby was a ‘very personal choice between you and your partner’, and another said that they would not base their child’s name ‘on what other people think or what the statistics say are the popular names’. Participants said that they relied on emotional connection rather than any data-driven insights:

‘I wouldn’t have said so, not in the naming terms, because I think that’s a very personal thing anyway. So… any statistics or anything anyone else says wouldn’t really come into play too much.’ (male, 35–44, driver)

However, when reflecting on the choice of baby names in more depth during interviews, it was apparent that participants had often encountered and used official baby name statistics in this process, even when they had not initially realised they had. This was apparent in their recollection of how they made the decision, and when they were subsequently presented with official baby names statistics, they explained that these were exactly what they had used.

Participants often described using Google searches as a first step for generating baby name ideas and creating shortlists. Participants used queries like “top 100 baby names” or “popular names”, which often directed them to baby websites, blogs, forums and name rankings:

‘I would have just gone onto Google and searched in most popular boys’ or girls’ names and then, yeah, there’s multiple websites that give you lists of the top 100 names.’ (female, 35–44, finance officer)

‘soon as I went on my phone, I’d go onto Google, and it would just come up straightaway with top ten names.’ (female, 35–44, teaching assistant)

Some participants likely encountered and used official baby name statistics in this process, but did not necessarily recognise them as such. However, they said that they used name trends and popularity to avoid overly popular names, or alternatively to ensure that they selected “timeless” names that would not go out of fashion, depending on their preference:

‘We looked at a lot of baby lists, we looked at the trending names… but it was mainly to figure out what we didn’t want, I think, rather than what we did.’ (male, 35–44, IT worker)

This finding demonstrates that the use of official statistics can sometimes be “hidden” from the public. This research shows that participants are likely to access official statistics (and other data) on websites that are designed to aid the specific decision-making process that they are undertaking, as opposed to going to websites that are focused on official statistics.

Back to top