Chapter 5: What influences when people use official statistics to make personal decisions?

Chapter summary and implications

Our interview and survey research has revealed a range of factors that influence whether and when people use official statistics to make personal decisions. These factors can be broadly divided into the following categories, which are presented in detail in the subsequent sections:

- Type and nature of decision

- Availability of other information

- Awareness of official statistics

- Relevance of official statistics

- Trust in and perceived reliability of official statistics

- Clarity and accessibility of official statistics

5.1. Type and nature of the decision

5.1.1. Using statistics when decisions are important

This study focused on relatively big life decisions, as these were thought to be more likely to involve examining a wide range of information, including potentially official statistics. This assumption was corroborated through participants’ interviews, where participants explained that they would be more likely to consult official statistics when making what they perceived as important decisions:

‘In my daily life I don’t really look at statistics, but making a bigger decision… that would be really helpful.’ (female, 35–44, advisor)

‘Moving house is one of the biggest changes in your life. I think it’s one of the most stressful as well and I don’t think you just would move somewhere blindly… I wouldn’t have just chosen where I live now just because I’d heard of the place. I’d have to definitely research and look into things before I made that decision.’ (male, 35–44, analyst)

Some participants highlighted the amount of effort put into decisions such as naming their child, describing it as ‘daunting’ and ‘difficult’, and requiring advice and extensive research:

‘It was quite hard because you just think that’s the name that the baby has to have for the rest of his life.’ (female, 35–44, finance officer)

Similarly, parents often approached the choice of primary school with great care, dedicating significant time in researching and weighing options using information from multiple sources:

‘It was a hard decision… The parent guilt that gets wrapped up in it, am I making the right decision?… So you want to make sure that you get it right… I think we put a lot of thought into it, and a lot of time into trying to make the right choice.’ (male, 35–44, IT worker)

The perceived importance of a decision also influenced whether participants reported relying on a broad range of information. While this was often implied, some participants explicitly noted variations in the weight they gave to different decisions. For instance, one participant viewed moving to a new area as a relatively low-stakes decision given their personal circumstances:

‘Maybe if I had children I would be looking into this kind of stuff a bit more before, you know, schools and healthcare and crime, but it felt like more of a low-risk spontaneous move I guess.’ (female, 35–44, HR worker)

Back to top5.1.2. Using statistics when decisions are impersonal

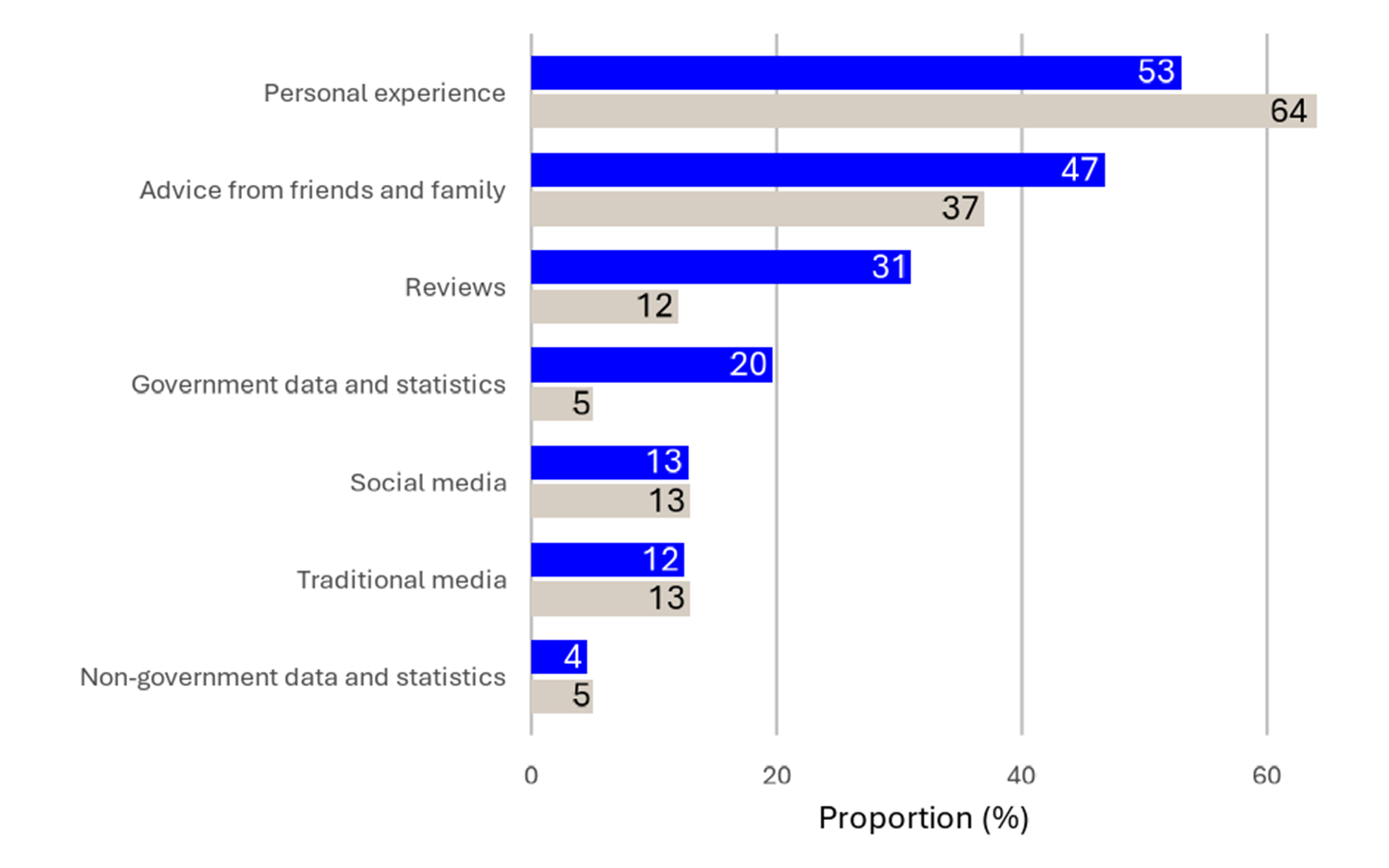

Our findings suggest that official statistics are less likely to be used for decisions perceived as highly personal. As an example, the survey showed that personal experience played a more crucial role than government data and statistics when choosing a baby name compared to other decisions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Information sources respondents would use to help choose a baby name.

Note: Sources of information respondents would want to use to help them choose a baby name. Respondents could select multiple options. Grey bar is responses for choosing a baby name while blue bar is average across all decisions. See [info] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

5.1.3. Using statistics when people have agency in their decision

Not all decisions offered realistic alternatives that allowed interview participants to choose according to their preferences. As an example, some participants noted that signing up to a GP often came down to choosing whichever surgery was accepting patients, and others highlighted that financial necessity sometimes drove decisions, such as continuing to work after retirement. In such cases, participants reported that they would typically be less likely to engage in information gathering and research, including consulting official statistics.

Back to top5.2. Availability of other information

The availability of other sources of evidence often influenced whether participants sought out additional information, such as official statistics. In our survey, 25% of respondents said that a barrier to using official statistics when making a decision was when other sources already gave them the information they needed. This was the second most commonly selected barrier.

This finding was corroborated in the interviews and open-ended survey responses. Survey respondents expressed not needing statistics when they already had the information required to make a decision, either due to personal experience or having access to other sources of information. For instance, one respondent stated that they wouldn’t use statistics when they ‘already know or have a good idea of something’, while another referred to already knowing ‘where to go and [get] the right info’.

Interview participants gave concrete examples of not seeking out additional evidence due to already having the required information available, for instance when they moved to areas they already knew well, such as their hometowns or places where friends and family lived:

‘I’ve been in this neck of the woods before, quite a good few years ago, so I kind of know about it. And friends have been here for a while… I knew family and friends, that research was done. I wasn’t going, for example, from Glasgow to Northumbria where I knew absolutely nobody.’ (male, 45–54, retail manager)

Back to top5.3. Awareness of official statistics

A key barrier to using official statistics for personal decision-making seen in this study was a lack of awareness — not only that such statistics exist and can be used for this purpose, but also that the information participants sometimes relied on may have been drawn from official statistics.

Some interview participants reported that they had never considered looking for official statistics to support their personal decisions:

‘I’ve never really thought about looking. I just didn’t think it was around, didn’t think this information would be around.’ (female, 35–44, teaching assistant)

However, when presented with data from official statistics, participants often expressed interest in using them now that they were aware of their availability. For instance, some expressed surprise to learn about the data that feeds into GP Patient Survey statistics (see Appendix 8.4), and indicated that they would consider using them in the future:

‘I’ve never seen anything like that before. I think that would be really helpful.’ (female, 35–44, advisor)

‘I must admit, if this information has been available, I didn’t know it was available. If this was widely known, I definitely would have checked this too.’ (male, 35–44, manager)

In open-ended survey questions, respondents highlighted the importance of increasing public awareness to enhance the value of official statistics. Suggestions included improving accessibility and visibility through better promotion:

‘I don’t know, maybe advertise more and make people aware as I wouldn’t think to use the Office for National Statistics for information.’ (survey respondent)

This quote also highlights low awareness of where official statistics can be found, as over 100 other organisations produce official statistics in addition to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), and their statistics are not found on the ONS website. This was a common theme throughout the interviews as well.

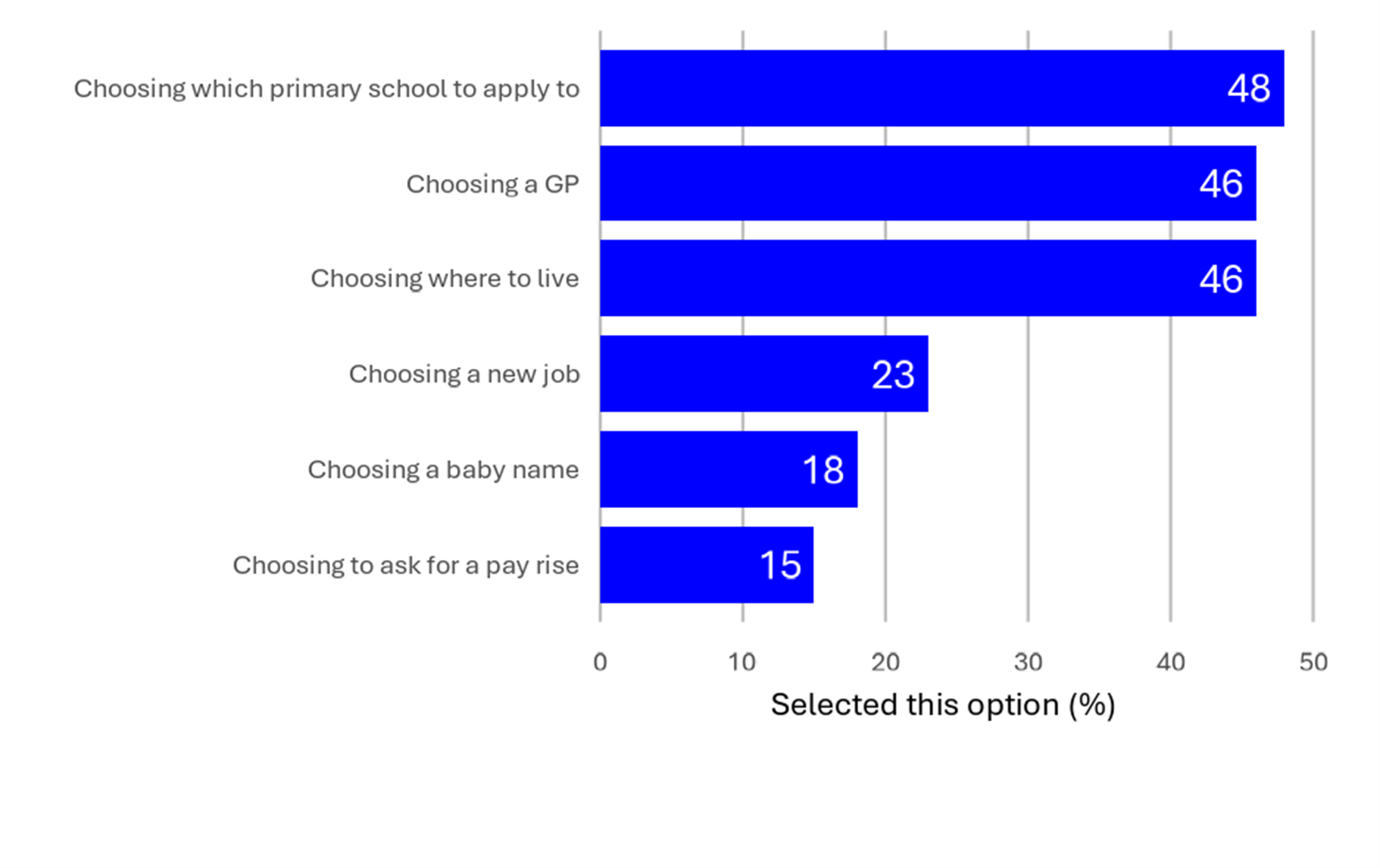

Similarly, when survey respondents were asked whether they were aware of any official statistics that could help them make specific decisions, they showed varying levels of awareness depending on the decision. Self-reported awareness was lowest for statistics that could help with choosing a new job, a baby name and asking for a pay rise, and highest for statistics that could help with choosing a school, GP and a place to live (see Figure 3). However, since this question appeared towards the end of the survey – after relevant examples had already been provided – responses should be interpreted with this context in mind.

Figure 3. Awareness of official statistics that could help people make six decisions.

Note: Awareness prior to the survey of any official statistics that could help people make each of six decisions. See [aware] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

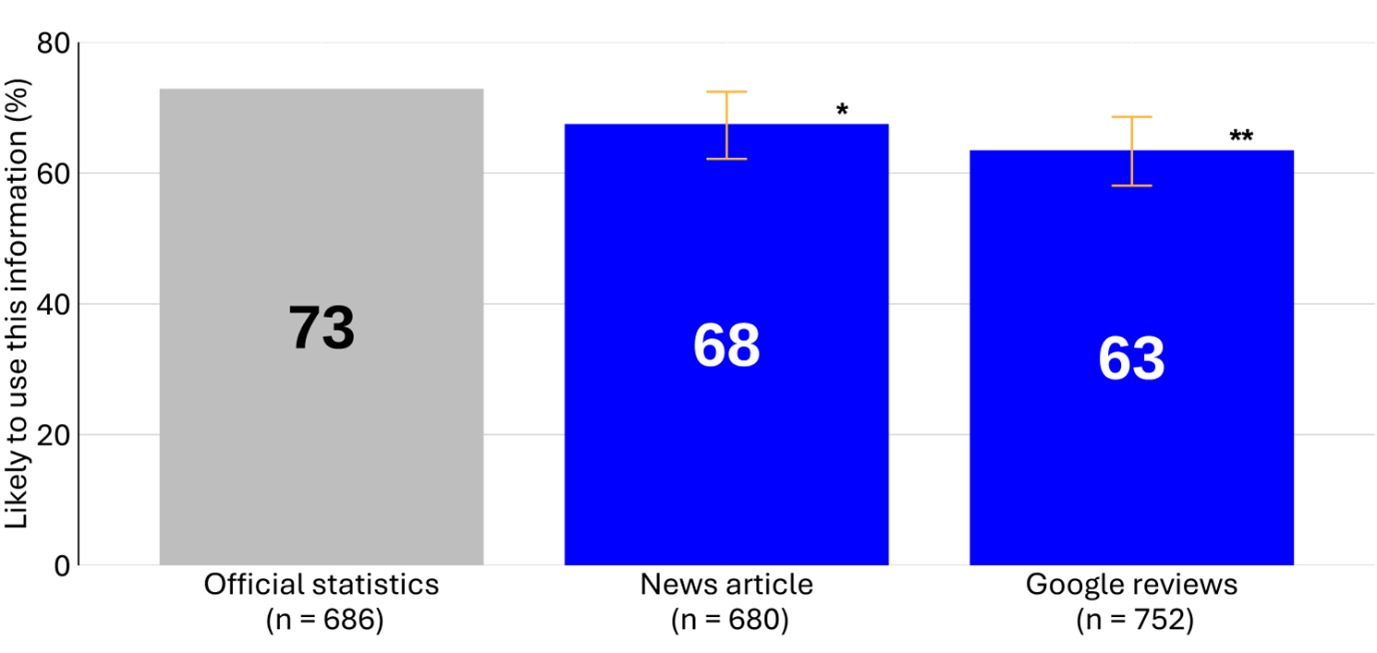

Second, our findings also suggest that participants were more likely to report using official statistics when they were made aware of them. Figure 1 in Chapter 3 shows that, when asked broadly about the sources that they would want to use to help make a decision, survey respondents most commonly cited personal experience, advice from friends and family, and reviews, followed by government data and statistics, social media, and traditional media. However, Figure 4 below indicates that when survey respondents were presented with specific sources within the context of a decision, they were more likely to say that they would use data from an official statistic compared to online reviews.

Although the survey questions are not directly comparable, this aligns with broader interview findings – participants seemed more inclined to report using official statistics when given concrete examples, rather than discussing them in abstract terms.

Figure 4. Likelihood of using the information to inform a decision.

Note: When choosing a GP, participants who were shown official statistics were significantly more likely to say they would use this information compared to those shown news articles (5 pp. less likely) or Google reviews (9 pp. less likely). See [intentGP] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents. **p<.01, *p < .05, + p < .1. p values have not been corrected for multiple comparisons.

5.4. Relevance of official statistics

5.4.1. Relevance to personal decisions

Interview participants typically reported being uninterested in using official statistics for personal decision-making when those statistics were not directly relevant to their own circumstances. For instance, one participant said that broader macroeconomic and aggregate statistics, such as employment and inflation statistics, had ‘absolutely no bearing on me whatsoever’. Others described these more as ‘news’ and ‘interesting’, but not personally relevant to their decisions:

‘If I can afford it, I will do it. If I want to do it, I will do it. I do not look at the wider picture. It is only me.’ (male, 65+, education assistant)

‘This graph for me is just like a graph, it just doesn’t feel like… until it affects you sometimes you don’t really start thinking about it.’ (female, 35–44, HR worker)

Participants highlighted that the more localised the data were, the more useful they became for decision-making. Crime maps, in particular, were mentioned by participants as valuable because they could provide information at a neighbourhood level:

‘I went quite granular. So I looked at, I think there’s a site, or is it on the West Midlands police where you can look at where every crime was reported, and I actually tracked it to the street as well.’ (male, 35–44, IT worker)

While crime maps themselves are not official statistics, they are created using data that are similar to those that feed into official statistics. As such, knowing that neighbourhood-level data were of interest to participants is still applicable to official statistics, even if in this specific example the data themselves did not come from official statistics sources.

Back to top5.4.2. Context

One way to highlight that statistics were relevant and actionable was to present them within a context that was familiar and relevant to decisions. For instance, in open-ended responses, survey respondents stressed the need for ‘context and practical examples’ as well as ‘clear explanations of the data’s relevance to everyday decisions’. They also suggested that statistics should be more tailored to specific decisions or actions, with features such as data visualisation tools and customisation options enhancing their usefulness. For instance, a survey respondent noted that filtering and tailoring data ‘would help me quickly interpret the data and apply it to current decisions’.

Generally, participants reported that comparisons often made it easier to understand the data that they were shown, especially when comparisons were drawn to familiar contexts. They reported that it helped them to interpret whether numbers were high, low or normal. Without this comparison (which was the case for some of the adapted materials shown to participants during interviews), participants sometimes found it hard to judge what they saw:

‘There’s no overall averages given here. I would like to see overall crime statistic, if possible, per 1,000 people, a percentage wise or a comparison, some sort of an overall.’ (male, 25–34, manager)

Participants did not always see national averages, an often-used comparison in the materials presented to them, as the most relevant benchmark. For instance, some expressed a preference for comparisons to other local areas that were familiar to them, as they had a better sense of what that would mean for their everyday experiences. The national average, in contrast, could be less meaningful for understanding everyday experiences, as participants had not necessarily lived in a place that fit the national average.

Another way of providing context was to view trends over time rather than isolated snapshots, a preference expressed by some participants. For instance, when choosing a baby name, some said they preferred ‘timeless’ names that were unlikely to ‘go out of fashion’. In selecting an extract of data for participants to explore in the interview, we chose baby name, rank and count. For both England and Wales and for Scotland, we also included change in rank since the last release. While participants expressed that they appreciated the small indicator of trend in the baby name statistics that was presented to them (the change in rank since last release), they would have liked to see longer historical trends to assess whether a name’s popularity was stable or fluctuating. Currently, trends for the top 100 baby names are available on the websites of official statistics producers as part of full statistical releases, data tables and interactive dashboards, as well as some non-official websites using the ONS data.

Another participant made a similar argument in relation to crime statistics when we presented participants with rates of different police recorded crime types for a single year. This participant expressed that they wanted to see whether crime rates in particular areas were rising or falling rather than relying on a single-year snapshot. This information is available as part of the full statistical releases, which show crime trends over time.

‘I guess I would want to then dive deeper into this… I’d want to see if there was a trend of it going up or down, because this is just a snapshot of one year, and I would like to know just how effective the criminal process is in that area, and how many convictions there are.’ (female, 55–64, assistant)

Back to top

5.4.3. Timeliness and frequency

Some interview participants emphasised the importance of using up-to-date information for personal decision-making. For instance, some noted a lag in the official baby name statistics presented during interviews. At the time of the interviews (summer 2024), the most recent official statistics on baby names for England and Wales covered 2022, whereas some non-official sources provided more current information for that geography. As baby name statistics are published by different producers across the UK, more recent statistics had been published for Northern Ireland and Scotland. Some participants highlighted that name trends can change rapidly, often influenced by popular culture, making timely data essential to ‘stay ahead of the trends’:

‘It’s always worth checking just how old the data is, because generally, it can lag. So, a lot of it can be from five or ten years ago. So, trying to check the reference of when it was last updated.’ (female, 55–64, assistant)

For some, it was particularly important to avoid choosing a name that had become too common, so they used baby name statistics to rule out names:

‘We didn’t want to create another Isla, or you know, whatever. Not that there is anything wrong with the name Isla, but we just wanted something a bit different.’ (male, 35–44, engineer)

A similar theme arose in free-text survey responses, when respondents were asked about what might increase their trust in official statistics. “Regular updates” was the joint-first most common word pairing in responses, implying that frequent statistics outputs may support trust. As discussed in the next section (5.6), trust also appears to be associated with use.

Back to top5.5. Trust in and perceived reliability of official statistics

Based on our survey data, trust seems to be associated with increased use of information sources for personal decision-making. Respondents reported the highest levels of trust in their previous experience (91%) and advice from friends and family (82%), while trust in other sources, including government data (56%), was lower. Although statistical tests have not been conducted to confirm the relationship, there appeared to be a pattern where sources with higher reported levels of trust were also the ones survey respondents expressed a greater willingness to want to use in decision-making (see Table 3).

| Source of information | Trust | Would want to use in decision-making |

|---|---|---|

| Previous experience | 91% | 53% |

| Advice from friends and family | 82% | 47% |

| Reviews | 59% | 31% |

| Government data | 56% | 20% |

| News | 50% | 12% |

| Non-government data and statistics | 47% | 4% |

| Social media | 46% | 13% |

Note: Self-reported trust for different sources of information among respondents, alongside whether they would want to use those sources to help them make six decisions. See [trust] and [info] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

This finding indicates that one way to encourage the use of official statistics in personal decision-making may be to improve public trust in them. This supposition is supported by free-text survey responses to a question about why individuals would use official statistics, with some respondents stating that they used statistics because they saw them as a good or trustworthy source of information:

‘It is because I believe the source of information is valid and trustworthy. I will use it regarding a place to get a land for purchase.’ (survey respondent)

Both open-ended survey responses and interview participants highlighted several key factors that they expressed could enhance their trust in official statistics:

- Relevance to personal circumstances: participants reported being more likely to trust and use statistics that felt directly relevant to their lives.

- Transparency in data collection: participants reported higher trust when they understood how data were collected and by whom.

- Independent oversight: participants reported valuing independent verification processes to ensure accuracy.

- Third-party fact-checking: participants reported valuing when official statistics were validated by credible third-party sources.

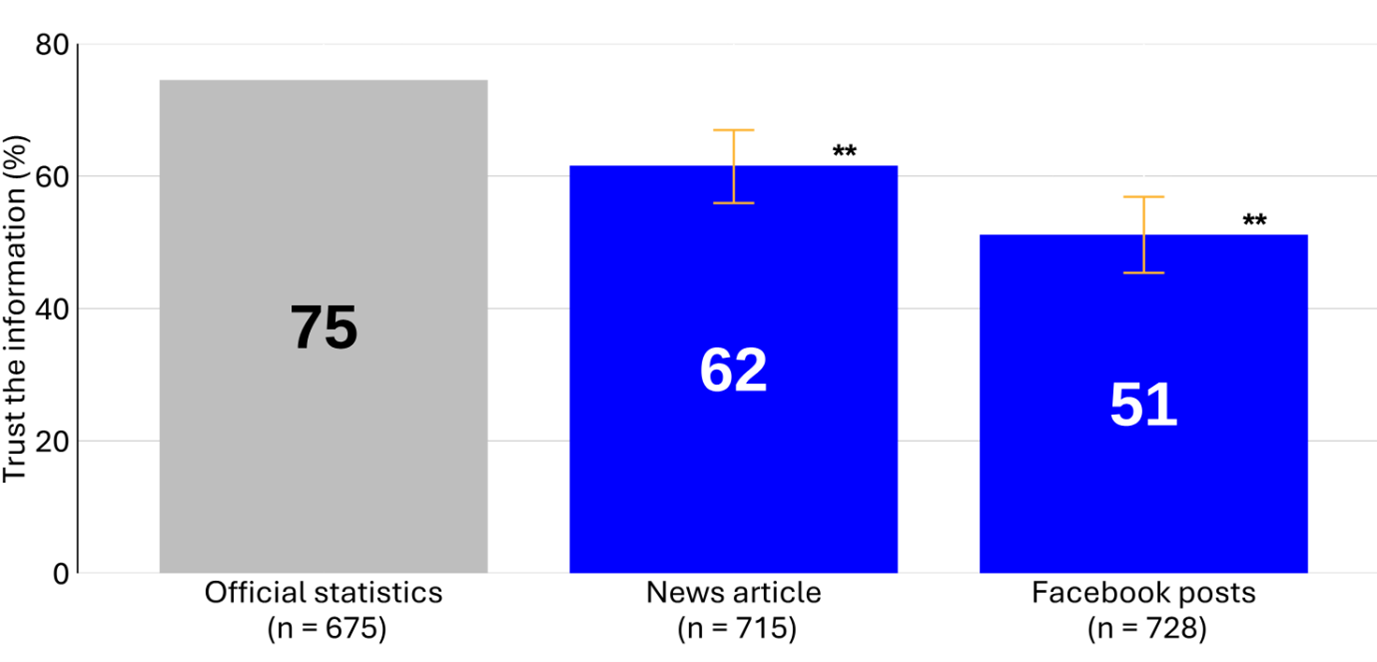

While about one in two survey respondents reported trusting government data when asked directly (56%), trust levels increased when interview participants were asked about their trust in specific statistics in the context of choosing a GP (72%) and choosing where to move (75%) . In an experiment we included in our survey, respondents were randomly assigned to be told about one of three types of information sources (official statistics, a news article and crowdsourced information such as Google reviews or Facebook posts) that may help them make specific decisions. Respondents were then asked how likely they would be to use that information, and about their level of trust in the information they received. The results for trust mirrored usage patterns: official statistics consistently outperformed other sources in both decision-making scenarios that we tested (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Likelihood of trusting different information sources to inform the decision to move.

Note: When deciding whether to move, participants who were shown official crime statistics were significantly more likely to say they would use this information compared to those shown news articles (8 pp. less likely) or Facebook posts (18 pp. less likely). See [intentCrime] in Appendix 2 for question wording. **p<.01, *p < .05, + p < .1. p values have not been corrected for multiple comparisons – this was exploratory analysis.

This discrepancy suggests two possible interpretations. One explanation is that, in the survey portion, people may not have been familiar with government data and what that meant, and therefore reported lower trust in them than when presented with specific examples. Alternatively, the specific statistics they were told about may happen to be sources that people already perceive as more trustworthy (for example, the NHS GP Patient Survey (see Appendix 8.4) and police recorded crime statistics), rather than “government data” as a general category.

Back to top5.6. Clarity and accessibility of official statistics

The ease or difficulty of understanding official statistics seemed to play a meaningful role in whether participants reported using them for personal decision-making. The way statistics are presented and explained can either facilitate or hinder their use.

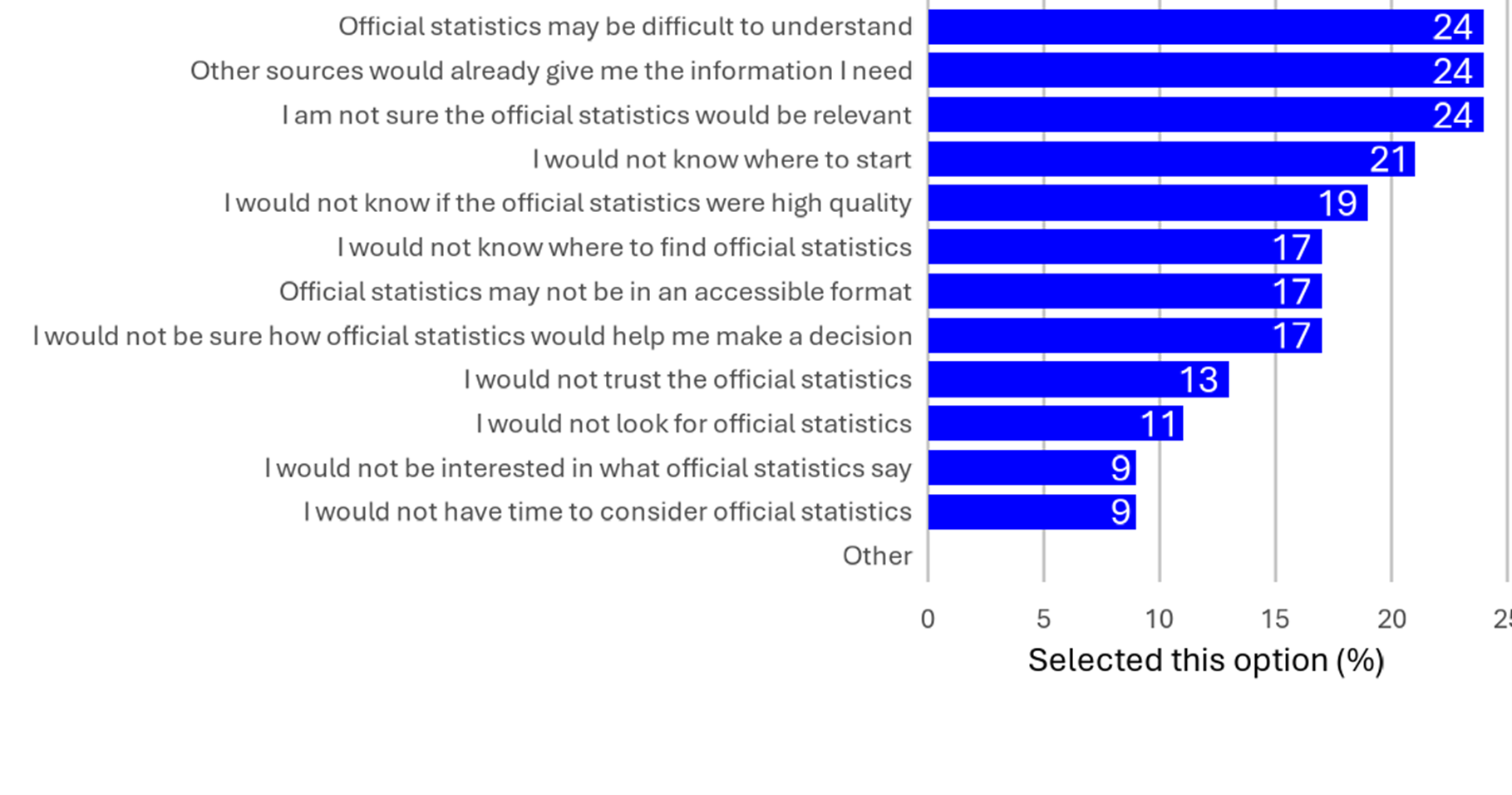

Figure 6 presents survey responses to a question about barriers to using official statistics in decision-making. The most commonly cited barrier among a series of pre-determined options was the perception, or expectation, that “official statistics may be difficult to understand”.

Figure 6. Barriers in using official statistics when making a decision.

Note: What might stop respondents from using official statistics when making a decision. Respondents could select multiple options. See [barriers] in Appendix 2 for question wording. Sample: 2,118 respondents.

The following sections explore key themes that emerged.

Back to top5.6.1. Simpler formats

Interview participants generally seemed to respond well to simpler formats like tables and bar charts, which were described as very accessible and easy to interpret:

‘It’s your typical chart, isn’t it? So it’s probably the most basic way you can display information and make it easily readable.’ (male, 45–54, fundraising specialist)

‘It’s a bar chart and it’s pretty straightforward. It’s got the job, and it’s got the amount, so it’s pretty easy to follow. Most people I’d imagine understand bar charts.’ (female, 55–64, administrator)

However, participants who were less confident in interpreting tables and charts seemed to find them easier to understand when they presented a small amount of information. Large datasets or complex visualisations that required them to actively navigate and interpret the data often appeared overwhelming for those participants:

‘It took me a few seconds to understand which way the table was working and how they were going to represent it, but, yeah, it worked. When I saw that blue line, that threw me, but then I realised what the blue… it was going across and not up. It was one of those things. But it took 30 seconds for my eyes to adjust.’ (female, 45–54, homemaker)

‘It’s difficult for me to understand. The dotted lines down the screen I don’t particularly like, yes, I can see it is for 10, 20, 30 pounds per hour, okay. It’s like every little bit you have to look at an extra bit to figure out what that bit means.’ (female, 35–44, advisor)

Back to top5.6.2. Frequencies

A common barrier to understanding charts was confusion about the scales on the axes. For instance, interview participants often paused to process when numbers were recorded as “per 1,000 people” rather than as percentages. Some participants verbalised this confusion and sought clarification:

‘Per 1,000 people, okay got you. [pause] Sorry, I’m thinking in my head there.’ (male, 25–34, director)

‘But the number at the bottom is confusing me a bit. Out of 1,000 people. Yeah, all I can say is I do not know.’ (male, 18–24, student)

‘When it says 120 on here, is that, so that’s 120 out of 1,000 is it, or is… that’s the bit I don’t quite understand.’ (male, 35–44, consultant)

Some participants attempted to convert these figures into percentages to make them more meaningful, but this often caused uncertainty even when they converted them correctly, like this participant:

‘The first thing I did was convert this into percentages, because I work better in percentages, so, is that right? So, it’s [37 people per] 1,000 people, so is that 4% really?’ (male, 35–44, engineer)

Participants also made mistakes in the conversion, such as this participant, who misinterpreted “11 per 1,000” as 11%:

‘I don’t know how many per 1,000, if I’m completely honest, I don’t know if it’s like 11%. I’m guessing 11.’ (female, 25–34, advisor)

Back to top5.6.3. Explanations of terms

Another barrier reported by interview participants was a lack of clear explanations of important terms in the extracts of data they were shown. Participants described finding it helpful when terms were adequately described:

‘I like the fact that they’ve expanded at the bottom what that actually entails so it takes away any questions. There’s nothing worse than data you can’t interpret.’ (female, 25–34, administrator)

However, some participants did not immediately notice explanatory notes:

‘I don’t actually understand what some of these mean… Oh, look, and then I’m now looking at the bottom, and it does actually say. Okay, so now I kind of get what it’s saying.’ (male, 35–44, engineer)

When explanations were missing, which was often because the materials had been adapted to fit the interview format, participants sometimes expressed frustration and disengagement, especially with technical terms such as “inflation” and “economic inactivity rate”:

‘The economic inactivity rate is not clear, it means nothing really. I have a vague idea or notion of what it means, but it actually has no clear meaning at all and is to me a useless statistic.’ (male, 55–64, CEO)

‘I don’t understand what it is. It’s meant to show me the inflation rate, but I don’t understand, is this for an average family? An average person? Is this for somebody living in London? It’s not terribly clear.’ (female, 65+, supervisor)

Similarly, what appeared to be perceived as statistical jargon among interview participants was also a source of confusion. This included terms such as “year ending September 2023”, “median”, “seasonally adjusted”, “goods and services”, age groupings (for example, 25–34) and sector descriptions (for example, food and accommodation). Some examples are provided below:

‘So, is the line where it says “UK median” is that just the average that someone in the UK earns, is that right?… That is how I interpret that anyway, I think that’s what that means, that’s the average. Is that the average?’ (female, 25–34, administrator)

‘This is like goods and services, I don’t know if that covers food, electricity, gas, water… So I don’t know what the goods and services defines.’ (female, 25–34, civil servant)

‘Construction, does that include electricians?’ (female, 35–44, finance officer)

‘I’m not sure why it is broken down into those particular age groups either. I can understand some of them, like age 65+ or age 18–24 but the bits in the middle, I’m not quite sure, does that make a particular difference, I don’t know.’ (female, 65+, supervisor)

In many instances, these terms were explained in the original statistical release. For example, the term “goods and services” is defined in official statistics publications on this topic. However, it is still beneficial to be aware that much of the terminology that is common to statistics may not be immediately understood by some audiences.

Back to top5.6.4. Amount of information

Our interviews demonstrate the challenge of presenting too much or too little information, with some participants stating that they wanted more details and others describing feeling overwhelmed.

On the one hand, some participants expressed wanting more-detailed breakdowns, especially ones that were relevant to their local context or personal circumstances. These participants often appeared to welcome interactive tools that allowed customisation:

‘It’s very clear. I mean, here, look, the filters that are available, sorting it by, you know, or you could choose how much, you know, the percent of the gap or the average earnings. It’s actually very easy to understand and to navigate.’ (female, 35–44, student)

On the other hand, other participants spoke about finding detailed information daunting, especially in interactive visualisations. Some expressed lacking confidence in navigating those tools, and doubted that they would use them independently outside the interview setting:

‘I think it’s a hell of a lot of information which probably would put me off investigating it further.’ (female, 35–44, student support worker)

‘I think the graph itself is just really, really busy. It’s actually hurting my eyes a wee bit.’ (female, 25–34, civil servant)

These participants expressed a preference for simplified summaries, or looked for shortcuts that could help them interpret key messages, rather than meticulously exploring the data themselves:

‘It is a little bit busy for me, but if you had something that was less information and just had an overall…rating, or even broken down into a couple of categories, that would be helpful.’ (female, 35–44, advisor)

‘I don’t think that would be very useful unless you want to sit and study that for a long time. But I suppose you’d want it just to be very clear in a number.’ (male, 35–44, driver)

‘There’s a lot of writing on the left-hand side. So it’s not an attractive table in the sense that it’s not easy on the eye. I think the writing on the left needs to be succinct and to the point. Maybe two words, three words.’ (female, 45–54, homemaker)

Back to top5.6.5. Assistance with interpretation

Participants generally appreciated when the information they were shown included guidance on interpreting key figures. This could involve narratives or context explaining underlying trends, or it could be through colour-coding to highlight key numbers:

‘I think it is fairly easy to understand. Red means bad. Green means good. Yellow means somewhere in between.’ (male, 35–44, IT worker)

However, one participant expressed concern about colour-coding, preferring to make their own judgement, rather than being guided somewhat arbitrarily by the statistics producer:

‘I think the reason why I like it is because it’s quite bland and clear, and there isn’t any traffic lighting system, which means I’m making that decision. I think when people try to be more helpful with other people’s decision-making, they often add a layer of subjectivity into it, which is something I don’t respond well to. So, if they put that 16% as a red. Well, why would you put that as a red?’ (male, 35–44, engineer)

Back to top