Chapter 2 – The future of data sharing and linkage across government

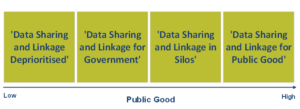

In Chapter 2 we will look to the future of data sharing and linkage in government, helping bring to life the barriers and enablers presented in Chapter 1. We present four possible ‘future scenarios’ for data sharing and linkage, set five years from now, based around the themes raised in our interviews. Future scenarios are not predictions but stylised versions of possible futures. We believe these help to bring out the impact on public good of acting on (or not acting on) the current barriers that exist to data sharing and linkage. They allow the reader to explore the possible implications of their choices when making decisions in this space. The four scenarios we consider are: Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good, Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos, Data Sharing and Linkage for Government and Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised.

To support and illustrate the scenarios, we have developed three ‘personas’, which outline the potential experiences of an academic researcher, a government researcher, and a service coordinator working in the charity sector. These emphasise the impacts and outcomes of different scenarios and illustrate the argument for making choices that lead towards data sharing and linkage for the public good.

Finally, we present our ‘roadmap’ to the scenario: Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good. This roadmap is informed by the discussions presented in Chapter 1. It highlights where the current data sharing and linkage landscape across government is now, where we would like it to see it go, and the recommendations we have made that will help to get there.

Four alternative futures

To keep the scenarios consistent with each other, each scenario has the same four themes running through them, as discussed in Chapter 1. These are:

- Public engagement and social licence: The importance of obtaining a social licence for data sharing and linking and how public engagement can help build understanding of whether/how much social licence exists and how it could be strengthened. We also explore the role data security plays here.

- People: The risk appetite and leadership of key decision makers and the skills and availability of staff.

- Processes: The non-technical processes that govern how data sharing and linkage happens across government.

- Technical: The technical specifics of datasets, as well as the infrastructure to support data sharing and linkage.

Scenario 1: Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good

In this scenario, public understanding and buy-in to the benefit of data being shared and linked is high. Different groups across society can see the positive outcomes and the cultural norm is to be trusting, pro-collaborative and engaged with data that affects them. Furthermore, the outcomes of research using linked data are transparently published and widely accessible to all, leading to a willingness among members of the public to allow their data to be shared and used for public good. Public confidence is supported by consistent demonstration from those sharing and linking data that security and privacy are high priority. Where the data are personally identifiable, Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are used to enhance security and protect privacy.

Strong partnerships exist within and between government organisations, and extend beyond this to include external researchers, partnership organisations, the wider public sector and the private sector. Senior leaders understand and champion the benefits of sharing and linking data, actively encouraging and promoting safe and secure research using linked data for the public good by promoting a can-do culture and being proactive in removing barriers. Staff feel valued and supported which has created a trusting and collaborative environment across government leading to greater staff retention.

Access to government data is consistent and streamlined, making it more transparent and easier for those both in and beyond government to find and engage with the data they need. Both the data and metadata are of high quality and are provided ‘linkage ready’, where appropriate, reducing the time it takes researchers to provide public good research and reducing the time burden on analysts. Funding is effectively prioritised and sufficiently maintained to allow far and wide-reaching impacts at both local and national levels.

Opportunities to enhance the public good of data and statistics are fully realised and missed data use is very rare.

Scenario 2: Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos

In this scenario, data sharing and linking is happening in silos across government, usually aided by partnership organisations. Public understanding about what is happening with data and what public good impact it is having is confused and even though some groups in society are grateful for the areas where engagement and transparency have been good, other groups are frustrated that more is not being done in specific areas. This confusion is leading to reservation for some when considering willingness to share data, even in areas that have good engagement due to the lack of clarity from government as a whole.

In the silos where good progress is happening, senior leaders are proactive and engaged, collaboration is high, and consistency of practices helps things run smoothly. However, this positive approach is not replicated in all areas and there are pockets where little to no progress is made.

Funding is not evenly distributed and usually goes to those who have already had success, leaving areas with high potential but disengaged leaders worse off. Staff experiences differ widely from feeling supported and driven in pockets where progress is good to feeling underutilised and frustrated where it is not. This is leading to high staff turnover between departments. Access to data is inconsistent and for researchers it is luck as to whether the data they want falls within a successful pocket of work. This is the same with data quality where some data are very well documented and structured whereas others are not.

Public good is being realised in certain topic areas, but data from other topic areas could provide a more enhanced picture and opportunities are likely being missed. The frustration and confusion among the public is undermining their trust in government and thus jeopardising government’s social licence in relation to data sharing and linkage.

Scenario 3: Data Sharing and Linkage for Government

In this scenario, data are shared and linked well across government but the value and benefit to those external to government is not being considered or realised. As a result, public understanding of the government’s use of data and the impact it is having on public services is limited. This is leading to a lack of willingness to share data with government and is helping misinformation to spread more easily. This, in turn, is increasing levels of mistrust and making government more vulnerable to public backlash. The ability of government to continue to share and link data is threatened due to their lack of openness and the wider impact this is having.

Within government, leaders are proactive and encouraging of sharing but only within the protected government environment, with outputs developed for internal use. As a result, government analysts find the data access process simple, consistent and streamlined and enjoy working within a high collaboration environment. Funding is also effectively distributed across government departments giving each department the incentive to make their data high quality and well-documented for other government analysts.

Outside of government the picture is very different. Academics and researchers do not have a defined or consistent pathway to data access and find it difficult to know who to talk to resolve their situation. Those that have found success have found it can take many years and research grants have expired before data have become available. Furthermore, government are not engaging with the wider public and haven’t made any outputs from their analysis available in the public domain.

This scenario is good for internal government management but public good is not being realised and ‘missed use’ of data is common. It is also fragile and faces the risk of a rapid loss of social licence for data sharing and linkage.

Scenario 4: Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised

In this scenario, data sharing and linkage is not a priority for government. There is a view from senior leaders that ‘something has been done’ and therefore there is no incentive to go any further. As a result, public understanding of the use of data is limited and there are no measurable improvements to public services or processes being seen. This is causing an unwillingness amongst the different sections of society to share data. These sections increasingly question why data that they know is being collected is not being used in more innovative ways to improve their lives.

Vacancies are not being filled and the analysts that are still working in this area feel frustrated, un-motivated and un-supported in their specialities with no sign of this improving. Government data skills are falling dangerously behind the private sector meaning any new government data are not being processed or managed effectively. Funding has also dried up and partnership organisations are finding it more difficult to embed their messages and practices within the departments themselves.

Although data exists and can be accessed by analysts and researchers, the amount available is limited to already existing projects and there are no formal processes for data access or linkage. This leads to a feeling of ‘right place, right time’ when trying to get data access and a prior knowledge of who to speak to. When data does become available it is not always clear what the data are and their structure is often unusable in their raw state. As a result, time is wasted doing the same tasks each time data access is granted. Collaboration within and beyond government has slowed and dialogue rarely happens outside of small teams. This is further isolating those trying to do projects that have public good potential.

Although there was the potential for data sharing and linkage for the public good, this has not been realised and there are many examples of missed opportunities where data could have a real impact.

Visualising the scenarios

Below are two visualisations that represent how the scenarios interrelate with one another. These have been included to show the importance of both internal collaboration and external engagement on the future public good that data sharing and linkage can provide. Put differently, both ‘internal collaboration’ and ‘external engagement’ underpin the likelihood of arriving in each scenario, which in turn has a level of public good attached to it.

Figure 1 shows the four scenarios based on their level of external engagement and internal collaboration across government:

- Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised – low external engagement and low internal collaboration

- Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos – high external engagement and low internal collaboration

- Data Sharing and Linkage for Government- low external engagement and high internal collaboration

- Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good – high external engagement and high internal collaboration

Figure 2 shows the four scenarios based on the level of public good achieved from low to high – Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised (lowest), Data Sharing and Linkage for Government, Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos, then Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good (highest)

Personas

To support and illustrate the scenarios presented above, we have developed three imaginary personas: an academic researcher, a government researcher and a service coordinator working in the charity sector. For each, we have imagined their background, ‘data mission’ and the experience they might have in each scenario.

Academic Researcher

Name: Steve

Occupation: Professor at a university

Location: Edinburgh

Background: Steve is the head of a small team of researchers based in the social science department of a university. Their research focuses on the ways in which adverse childhood experiences impact on adult mental health. Steve is particularly interested in the links between childhood deprivation and the diagnosis of severe psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The team typically conduct their research using large, linked administrative datasets.

Data mission: Steve and his team have received funding for two years for a project which maps out indicators of childhood deprivation, such as receiving free school meals, and residing in a household in which one or more parent is in receipt of disability or incapacity benefit, with adult mental health outcomes, such as the prescription of psychiatric medications or a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder. Steve wants to link data from the Department for Education (DfE), the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the NHS.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good

Steve and his team provide evidence that public good can be achieved through their research and as a result, they are granted access to a linked administrative dataset through a secure data access platform. The dataset contains linked data from the DfE, DWP and NHS. This means that Steve’s team receive their data in a timely manner and can complete their research within their funded period. Their work is widely used by organisations within and beyond the public sector.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos

Although Steve’s team successfully obtain permission to work with a linked dataset, they struggle to link the datasets required for them to complete their analysis. The mechanisms are not in place for data sharing between the two government departments and the health service, the result of this being that full data linkage cannot be performed during their funded period. They successfully link two of the three data sources, resulting in some outputs.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Government

Steve and his team struggle to form working relationships with each of the three organisations from which they require data. They are aware of data linkage happening within government but have been unable to gain permission to use the data themselves. As a result of this, they cannot perform the data linkage within their funded period.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised

Steve and his team are unable to form working relationships with any of the organisations from which they seek data. The team are also aware that data linkage is not being routinely performed within government and as a result they are not able to use a previously linked dataset. They are unable to answer their research questions in their funded period.

Government Researcher

Name: John

Occupation: Social Researcher, Ministry of Justice (MoJ)

Location: Sheffield

Background: John leads a team of researchers at the MoJ, who are working to understand the impacts of parental imprisonment on the educational outcomes of children. They would like to compare the educational outcomes of children whose parents have criminal records but without a custodial sentence with those with a parent who has been in prison.

Data mission: John and his team want to link up data held by the Department for Education (DfE) with records from HM Prison Service (HMPS), for children whose parents have been in prison, and the Police National Computer (PNC), for those whose parents have committed crimes but have not been in prison. The team are aiming to link data over a period of ten years, to enable them to understand the long-term impacts of parental imprisonment.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good

John and his team are successful in their attempts to link education attainment data with data from both HMPS and the PNC. They can build an anonymised, longitudinal dataset, containing data on the attainment of children whose parents have criminal convictions and whether they have served custodial sentences. There has been a high degree of public trust in the project due to the levels of transparency around the project and the amount of engagement conducted with stakeholders.

Response to Sharing in Silos

John and his team can link data from HMPS with data from the DfE, allowing them to understand the link between parental imprisonment and educational outcome. However, they are not able to link with the data from the PNC. This means that while they have a good understanding of the impacts that parental imprisonment may have on a child, they aren’t able to determine whether these impacts occur because of the time their parent has spent in prison, or the criminal conviction.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Government

John and his team are successful in their attempts to link all three of their datasets, which allows them to answer their research questions. They produce a report and use their findings to inform policy around families and the criminal justice system. There is however very little engagement outside of government and the public are mostly unaware that the data are being linked. The lack of public awareness of the project means that stakeholders, such as children’s charities and non-government researchers, are unable to use the findings from the research.

Response to Linkage Deprioritised

John and his team are unable to link data from the MoJ with the HMPS and the DfE. Instead, they are encouraged to use a previously linked dataset, which allows them to partially answer their research questions. There is little interest from external organisations, as there is little awareness of data linkage performed by government departments.

Employee in the Charity Sector

Name: Martha

Occupation: Service Coordinator, charity sector

Location: Manchester

Background: Martha works for a small charity which helps individuals experiencing homelessness. The charity provides practical assistance for their service users, including food and short-term accommodation. They also provide advice, enabling their service users to access healthcare and benefits in the short term, and permanent housing and employment in the long term. Martha’s team have recently started conducting their own research with their service users.

Data mission: Martha needs to know about the lives of those affected by homelessness. She is particularly interested in the health impacts of rough sleeping, as well as the long-term housing and employment outcomes for individuals who have previously experienced homelessness. This information will allow the charity to tailor the advice and the support they deliver to the needs of their service users.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Public Good

Martha can access an abundance of information about the long-term outcomes of people affected by homelessness. She can use data from a longitudinal study on the employment outcomes for individuals who have previously experienced homelessness to inform the advice she gives to her service users, which leads to an increase in the number of service users gaining employment. The charity is considering submitting their own operational data for use in a large research project, having seen the benefits of research using linked datasets. They have confidence in the safety of the data.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage in Silos

Martha is aware that there are some public sector research projects which use linked data. However, these projects often do not include individuals who have previously experienced or are currently experiencing homelessness, so she is unable to build complete pictures. There is little clarity around the reasons for some areas being prioritised over others, which leads to distrust, with the charity being reluctant to share data in the future.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage for Government

Within government, research is being conducted about the longitudinal outcomes of individuals who have previously experienced homelessness. However, this research is mostly being conducted for internal use, which means that practitioners employed in the charity sector are not aware of the work and cannot use or help others benefit from the results of it. They are also disinclined to share their data, as they are not aware of previous incidences when data sharing has been of benefit.

Response to Data Sharing and Linkage Deprioritised

There is no longitudinal, linked dataset on the long-term outcomes of individuals who have previously experienced homelessness. This means that although Martha can use other sources of data to inform her practice, she does not have data about longer term outcomes, which would have been useful for her service users. The charity is also reluctant to share their data, as there are few examples in the public domain of cases of successful data linkage.

A roadmap to Data Sharing and Linkage for the Public Good

This section maps out how our recommendations can take us from where the data sharing and linkage landscape is now, within government, to where we think it should aim to be. We do this by linking our recommendations to our ideal scenario ‘Data sharing and Linkage for Public Good’.

There is a need for more public engagement about data sharing and linkage, to improve both transparency of work that is being carried out, and public confidence in data sharing and linkage more generally. There is growing evidence that people in the UK want and expect data to be used when it is done securely and transparently. There is an expectation by some among the public that their data are already being shared and linked within the public sector for the public good. There are examples of where public engagement is being done well, informing greater understanding of social licence. However, there was acknowledgement that there can also be a lack of understanding about how to do public engagement effectively. “Public understanding and buy-in to the benefit of data being shared and linked is high. Different groups across society can see the positive outcomes and the cultural norm is to be trusting, pro-collaborative and engaged with data that affects them. Furthermore, the outcomes of research using linked data are transparently published and widely accessible to all, leading to a willingness among members of the public to allow their data to be shared and used for public good.” The government needs to be aware of the public’s views on data sharing and linkage, and to understand existing or emerging concerns. Public surveys such as the ‘Public attitudes to data and AI: Tracker survey’ by the Centre for Data, Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) provide valuable insight. They should be maintained and enhanced, for example to include data linking. When teams or organisations are undertaking data sharing and linkage projects, there is a growing practice of engaging with members of the public to help identify concerns, risks and benefits. To help teams or organisations who are undertaking public engagement work, best practice guidelines should be produced, and support made available to help plan and coordinate work. This should be produced collaboratively by organisations with experience of this work for different types of data and use cases and brought together under one partnership for ease of use. We consider that, given its current aims, the Public Engagement in Data Research Initiative (PEDRI) could be well placed to play this role.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 1: Social Licence:

Recommendation 2: Guidelines and Support:

The amount social licence for a data sharing or linkage project can be related to data security. The Five Safes Framework is a set of principles employed by data services, such as TREs, that enable them to provide safe research access to data. Assurance that it is still able to deliver the appropriate level of security would be welcome. Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are newer technologies that can help organisations share and use people’s data responsibly, lawfully and securely. There is growing interest in PETs and the potential benefits their use across government (and internationally) could bring. “Public confidence is supported by consistent demonstration from those sharing and linking data that security and privacy are high priority. Where the data are personally identifiable, Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are used to enhance security and protect privacy.” Since the Five Safes Framework was developed twenty years ago, new technologies to share and link data have been introduced and data linkage of increased complexity is occurring. As the Five Safes Framework is so widely used across data access platforms, we recommend that UK Statistics Authority review the framework to consider whether there are any elements or supporting material that could be usefully updated. To enable wider sharing of data in a secure way, government should continue to explore the potential for Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) to be used to enhance security and protect privacy where data are personally identifiable. The ONS Data Science Campus is well placed to lead and coordinate this work.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 3: The Five Safes Framework:

Recommendation 4: Privacy Enhancing Technologies:

Strong collaboration between the UK statistical system and ADR UK has supported linkage and sharing of administrative datasets within and across organisations in all four UK Nations and is helping to make them available to accredited researchers within and beyond government in a safe and secure way. “Strong partnerships exist within and between government departments, and extend beyond this to include external researchers, partnership organisations and the local and private sectors.” We do not have a specific recommendation against this ambition, but our other recommendations seek to enhance collaboration across government.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendations

At every step of the pathway to share and link data, the people involved, and their skills and expertise, are instrumental to determining whether projects succeed or fail. The biggest barrier to data sharing and linkage for some organisations is whether it is a priority for the Accounting Officer. Making secure data sharing and linkage a strategic priority at the level of the Accounting Officer in more organisations would enable better joined up approaches across government. For this to happen, an appreciation of the potential benefits of data sharing and linkage for the public good needs to be more widely held across Accounting Officers. “Senior leaders understand and champion the benefits of sharing and linking data, actively encouraging and promoting safe and secure research using linked data for the public good by promoting a can-do culture and being proactive in removing barriers.” To gain the skills to create and support a data-aware culture, it is important for senior leaders to have awareness of and exposure to data issues. One way to raise awareness and exposure would be for senior leaders to ensure that they participate in the Data Masterclass delivered by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Data Science Campus in partnership with the 10 Downing Street (No10) Data Science Team. The Data Masterclass could expand its topics to include sections specifically on awareness of data linkage methodologies, the benefits of data sharing and linkage and awareness of different forms of data. This would fit well under the Masterclass topics of ‘Communicating compelling narratives through data’ or ‘Data-driven decision-making and policymaking’. To facilitate greater data sharing among organisations within government, a clear arbitration process, potentially involving ministers, should be developed for situations in which organisations cannot agree on whether data shares can or should occur. Developing such an arbitration process could be taken on by the Cabinet Office, commissioned by the Cabinet Secretary and delivered working with partners such as No10 and ONS.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 5: Data Literacy in Government:

Recommendation 6: Data Masterclass Content:

Recommendation 7: Arbitration Process:

Recruiting people with the skills needed to link, maintain and analyse data was a significant challenge raised by many of our interviewees. As well as recruitment, there is also a problem with retention. We heard that staff regularly move between government departments for the opportunity of better pay as civil service pay scales differ from one department to the next for the same grade. Career development in data roles is not always prioritised within government. “Staff feel valued and supported which has created a trusting and collaborative environment across government leading to greater staff retention.” To enable more effective and visible support for the careers of people who work on data sharing and linkage, those responsible for existing career frameworks under which these roles can sit, such as the Digital Data and Technology (DDaT) career framework and the Analytical Career Framework, should ensure skills that relate to data and data linkage are consistently reflected. They should also stay engaged with analysts and professionals across government to ensure the frameworks are fit for purpose. These frameworks should be used when advertising for data and analytical roles and adopted consistently so that career progression is clear.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 8: Career Frameworks:

There is variation within government over how much data holders and researchers understand the process necessary to share data under their respective legal bases. When applying for data through a secure data platform, the process is often lengthy and can appear overly burdensome. For every data share there will be many teams involved such as analytical, ethical and technical teams and these can be within the same organisation or from many different ones. We have heard that not getting these teams together at the very start can cause major delays to data sharing. When researchers have a question about a dataset or process it can be a challenge to find the right person within a department or team who can help. We also found that there is uncertainty around data ownership and where Information Asset Owners (IAO) sit within a department. “Access to government data is consistent and streamlined making it more transparent and easier for those both in and beyond government to find and engage with the data they need.” To help researchers understand the legislation relevant to data sharing and linkage and when it is appropriate to use each one, a single organisation in each nation should produce an overview of legislation that relates to data sharing, access and linkage, which explains when different pieces of legislation are relevant and where to find more information. This organisation does not need to be expert in all legislation but to be able to point people to those that are. The Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) will help convene those in this space to understand more about who might be best placed to take this on. To support re-use of data where appropriate, those creating data sharing agreements should consider whether restricting data access to a specific use case is essential or whether researchers could be allowed to explore other beneficial use cases, aiming to broaden the use case were possible. To ensure data application processes are fit-for purpose and well understood, those overseeing accreditation and access to data held in secure environments should prioritise ongoing communication with users, data owners and the public to explain and refine the information required. Wherever possible, they should offer face-to-face or virtual discussions with those applying to access data early in the process, to ensure clarity around both the data required and the process to access it. To ensure all necessary teams are involved at the outset of a data sharing and linking project, organisations should consider the use of a checklist for those initiating data sharing. The checklist should contain all contacts and teams within their organisation who need to be consulted to avoid last minute delays. Every organisation within government should be transparent about how the data they hold can be accessed and the process to follow. This guidance should be presented clearly and be available in the public domain with a support inbox or service for questions relating to the process.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 9: Overview of Legislation:

Recommendation 10: Broader use cases for data:

Recommendation 11: Communication:

Recommendation 12: Checklists:

Recommendation 13: Transparency:

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government Funding structures across government tend to be set-up so that each department controls its own spend, making successful funding highly dependent on the priorities and vision within each department. This siloed approach to funding means data sharing/linking projects are susceptible to breaking down if just one team is unable or unwilling to get the backing needed. Spending review cycles are often tight and have strict requirements where tangible benefit needs to be shown at every decision point. For projects which are complex or require many different datasets it may not always be possible to show benefit or meet the deadlines involved. This siloed approach is hampering efforts of collaboration and is a primary reason why projects with external funders are often much more successful. “Funding is effectively prioritised and sufficiently maintained to allow far and wide-reaching impacts at both local and national levels.” To allow every organisation a consistent funding stream for their projects, a centralised government funding structure for data collaboration projects across government, such as the Shared Outcome Fund, should be maintained and expanded.

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 14: Funding Structure:

It can be a real challenge for those linking data to get enough information about the data they are working with to provide a high-quality linked output with a measurable rate of error. Variation in data standards and definitions used across government is making linking harder. “Both the data and metadata are of high quality and are provided ‘linkage ready’, where appropriate, reducing the time it takes researchers to provide public good research and reducing the time burden on analysts.” To enable effective, efficient, and good quality data linking across government, senior leaders should ensure there are sufficient resources allocated to developing quality metadata and documentation for data held within their organisations. Many departments are looking to standardise government data and definitions, but it is unclear whether or how these initiatives are working together. Those working to standardise the adoption of consistent data standards across government should come together to agree, in as much as is possible for the data in question, one approach to standardisation which is clear and transparent. Given the work done by the Data Standards Authority, led by the Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO), the CDDO may be best placed to bring this work together.

The current data sharing and linkage landscape across government

What do we want it to look like?

Recommendation 15: Sufficient resources:

Recommendation 16: Standardisation: