There has been a lot of talk about a UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) technical report. It includes information on COVID-19 case rates in England for vaccinated and unvaccinated groups (Table 5). For some the immediate reaction to these data has been outright disbelief, others have used the data to support pre-existing, and incorrect, views that vaccines are not effective. Neither of these reactions is right. Understanding the issues properly is extremely complex, but what we do know with some certainty, is that while the vaccine will not stop the spread of the virus completely, it has been shown to help improve outcomes.

We have seen considerable improvements to the presentation of the data in the latest UKHSA report, which should support better interpretation of these data in future. However, it provides an important lesson about the harm that can be done if data are not clearly presented and well explained. There is more to communicating data than just presenting the numbers. Producers of data should do everything they can to minimise the potential for misinterpretation or misuse.

As well as presenting data clearly, producers need to guide users on how the data they publish can, and perhaps most importantly cannot, be used. They also need to explain the choices that are made in producing the analysis, along with the implications of these choices. Producers of data are the experts in the data they publish, their insight and understanding of these data can help ensure its appropriate interpretation and use.

To return to the example of COVID-19 case rates by vaccination status, the choices made by UKHSA have been a source of much debate because the consequences of the choices are so significant. It is important these choices and their implications are explained, and it is perhaps even more important that the guidance on interpretation of the data is clear. As an organisation of experts, UKHSA is in a position to help the public understand what the data mean, including explaining why the findings may not be as counter intuitive as they first appear while leaving no uncertainty around its views that vaccines are effective. UKHSA can help explain where there is value in using the data (e.g. looking at changes in case rates over time or across age bands, within the vaccinated group) and where there is not (e.g. understanding vaccine effectiveness).

Guidance on interpretation

The report is clear that a direct comparison of rates for vaccinated and unvaccinated is not appropriate. The report opens with the text:

“These raw data should not be used to estimate vaccine effectiveness as the data does not take into account inherent biases present such as differences in risk, behaviour and testing in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations.”

This is a helpful health warning. By thinking about questions people may have and how they may try to use data, producers can pre-empt potential issues and provide explanation that will support appropriate interpretation. In the context of COVID-19 case rates some of the key questions might be:

- What are the data measuring? And is this what people want to know about? Many people want to know the risk of COVID-19 infection for those who are double vaccinated compared with those who have not had a vaccine. The data in UKHSA’s Table 5 do not do this. It does not show infection rates in the population. The table shows case rates i.e. the rate of COVID-19 positive tests in those who come forward for testing, something the government continues to ask people to do[1]. As a result, the data may have inherent biases.

- Are the two groups in question comparable? It is easy to see that there may be different behaviours in people who have had two vaccinations compared to those who have had none. One hypothesis is that those with two vaccinations are more likely to get tested, meaning the case rates will look relatively higher for this group compared to the unvaccinated group. There will also be different risks associated with each group, the vaccination programme prioritised vulnerable groups and frontline health and social care workers, so includes those who are more at risk of infection. We haven’t seen evidence to quantify the impact of these risks and behaviours, but it’s likely there will be an impact.

- Are there other sources of data which could be considered? There are increasingly other sources of information which demonstrate vaccines are highly effective. The UKHSA has done a significant amount of research and analysis into vaccines. This is outlined in the vaccine surveillance report, which sets out effectiveness against different outcomes (infection, symptomatic disease, hospitalisation and mortality). There is further information via UKHSA’s monitoring of the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination In addition, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has published an article on the impact of vaccination on testing positive as well as an article on deaths involving COVID-19 by vaccination status. All of these examples take into account characteristics of those in the sample and try to adjust for differences. As a result, they offer a better indication of vaccine effectiveness.

Implications of choices

To undertake any analysis choices need to be made. These choices and their implications should be explained.

In the calculation of COVID-19 case rates the most significant choice is the decision on what population estimates to use to calculate the rates (“the denominator”). There are two obvious choices: the National Immunisation Management Service (NIMS) or the ONS mid-year population estimates. Each source has its strengths and limitations and we don’t yet know the true figure for the denominator.

In the context of case rates the choice of denominator becomes even more significant than when it is used for take up rates, because the numbers of people with no vaccine are low. The population of people vaccinated is relatively well known, NIMS includes all those who have been vaccinated and is a good estimate of this population.

The difficulty comes in understanding the total number of the population who have not had a vaccination. There are many advantages to using NIMS, not least because it is consistent with international approaches to considering immunisations and allows for analysis which would not be possible using aggregate population estimates. However, we also know that NIMS overestimates the population. Similarly, there are strengths in using ONS mid-year estimates, but we know these can have particular difficulties for small geographic breakdowns. We also know that the time lag created by using mid-year 2020 estimates has a disproportionate impact in older age groups – for example, it means that in more granular age bands some older age groups show more people having been vaccinated than the ONS population suggests exist. There is more information on the strengths and weaknesses of each source in NHSE&I’s notes on denominators for COVID-19 vaccination statistics. The chief statistician at Welsh Government has published a blog which outlines the impact of the different choices for vaccine uptake in Wales.

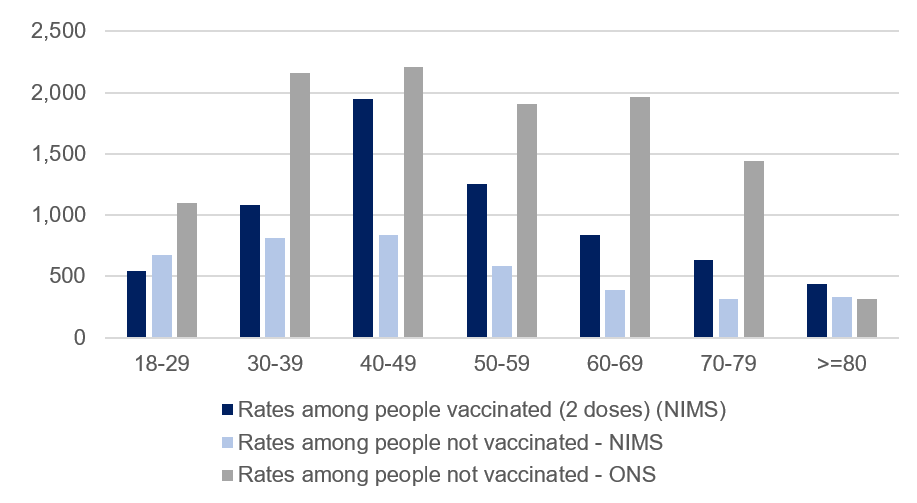

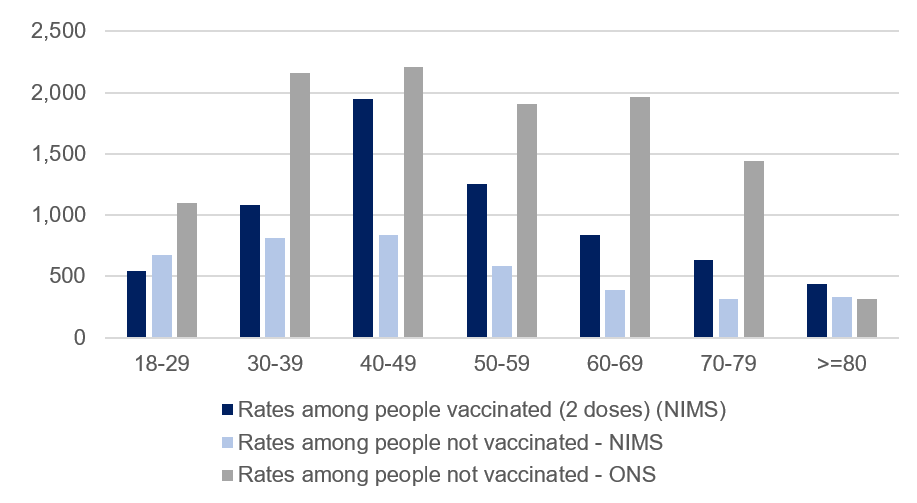

Looking just at the adult population, Figure 1 shows the different results which come from using the two different denominator options for the population who have never had a COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure 1: COVID-19 case rates per 100,000, England by age band

*see notes at end for the data and more details of sources used in this figure.

Using the NIMS denominator, the positive case rates for those who are not vaccinated is below the case rate for those who are vaccinated (except in the 18-29 age band). Using the ONS mid-year 2020 estimates as a denominator, the positive case rates for those who are not vaccinated is higher than for those who are vaccinated (in all age groups below 80). While we don’t yet know the true figure for the unvaccinated population, this seemingly simple choice has a huge impact. It is particularly problematic in this circumstance because any error in the total population estimate is applied in its entirety to the unvaccinated population.

As an example, for the 70 to 79 population, the NIMS figure is just 4% higher than the ONS mid-year estimates (5.02 million and 4.82 million respectively). These figures can then be used in combination with the data on total people vaccinated from NIMS to estimate the total number of people not vaccinated. In doing this, the difference of nearly 200,000 in the total population estimates is applied entirely to the relatively small number of 70 to 79 year olds who are not vaccinated. It means the NIMS estimate for the unvaccinated population in the 70 to 79 age band is 363% higher than the estimate of those not vaccinated based on the ONS mid-year estimates. So, an estimate 4% higher at the 70 to 79 age band has led to an estimate 363% higher in the estimate of the unvaccinated population at that age band. This has a huge impact on the case rates for this group, and the conclusions drawn from the data.

An understanding of the impact of choices is essential in supporting appropriate interpretation of the data. In this scenario, we don’t have enough information to know the true figure for the unvaccinated population in each age group. We hope that the work UKHSA is doing to improve the NIMS data (including removing duplicates) along with the work ONS is doing on population estimates and the 2021 Census, will improve our understanding. It is really positive that ONS and UKHSA are working together to try and solve this issue, which is so important across so many statistics. Given this uncertainty, knowledge of the implications of the different choices can help users interpret the presented data with caution.

The message from all this is that data has huge value, but it is also really important that those publishing data consider how the data may be used, what the strengths and limitations of the data are and think about how to present data in a way that minimises the potential for misuse.

In time, there will be changes to what we know about the population, and producers of analysis should not shy away from updating their outputs when new evidence comes to light. In doing this, they should also clearly explain any changes and choices, as this transparency will support trust and understanding. It will help the good data shine out and ensure statistics serve the public good.

[1] https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/testing/get-tested-for-coronavirus/

Data, sources and notes for case rate calculations:

Table 1: COVID-19 case rates per 100,000, England by age band

- The calculations in Figure 1 and Table 1 are based on publicly available data. There are slight variations compared to the UKHSA data in Tables 2 and 5. For example, it is not clear exactly what date UKHSA has used for total vaccinated or unvaccinated populations, and there are regular revisions to the published data on the coronavirus dashboard, which may have caused changes since data were used in the UKHSA analysis. These differences are not big enough to impact on the conclusions in this blog.

- NIMS data from coronavirus dashboard download, downloaded 31 October 2021. Metrics downloaded: “vaccinationsAgeDemographics”. Variables used:

- Total population = VaccineRegisterPopulationByVaccinationDate (for 24 October)

- Total vaccinated population = cumPeopleVaccinatedSecondDoseByVaccinationDate (for 10 October i.e. 14 days before end of period, as only cases with vaccination 14 days or more before positive test are included in UKHSA table of cases)

- Total not vaccinated = Population estimate – cumPeopleVaccinatedFirstDoseByVaccinationDate

- Total number of cases by age, and, cases by vaccination status by age, taken from COVID-19 Vaccine surveillance report week 43. UKHSA report shows total cases for four weeks to 24 October 930,013. Data downloaded (31 October) from coronavirus dashboard for four weeks up to 24 October (inclusive) gives 935,386. Additional cases likely due to cases reported between UKHSA analysis and 31 October.

- ONS population estimates based on ONS 2020 mid-year estimates taken from NHSE&I weekly vaccine statistics, 28 October 2021 (downloaded 31 October).