We have since published a Review of Income-based poverty statistics from the time of this blog’s release.

What does it mean to be in poverty? It’s a question that has been debated for a long time and is one of the reasons why measuring poverty is so difficult. There are many interest groups and think tanks who have covered this issue time and time again, such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Full Fact.

The concept of poverty means different things to different people and to some extent, requires a judgement call to be made as to where to draw the poverty line. Generally speaking, being in poverty refers to when people lack financial resources to afford to meet their basic needs.

While it may be difficult to define, it is important for central and local governments to understand the prevalence and nature of poverty in the areas they serve so that they can put targeted support in place. This blog looks at what data is out there to measure poverty and highlights the work being done to improve the future evidence base on poverty.

So what is the best measure of poverty?

There is no right or wrong measure of poverty. Different measures of poverty capture different things, and trends in these measures can vary over time.

No single figure about poverty tells the whole story so context is really important when drawing comparisons of poverty over time.

There are four commonly used income-based measures of poverty produced annually by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in its Households Below Average Income (HBAI) National Statistics publication:

- Relative poverty (relative low income) – households which have less than 60% of contemporary median income

- Absolute poverty (absolute low income) – households which have less than 60% of the median income in 2010/11 held constant in real terms

- Both relative and absolute poverty can be measured on a before housing costs (BHC) or after housing costs (AHC) basis.

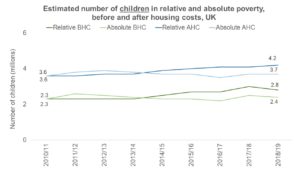

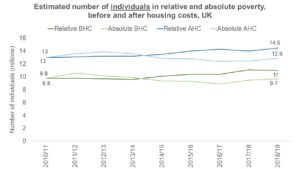

These four measures are published by children, pensioners, working-age adults and all individuals. The data below shows the latest figures for children and all individuals. Across all measures, we can see that the number of children in poverty has increased since 2010/11. For all individuals in poverty, the picture is more complicated as the total number in absolute poverty has seen a decrease in this time (by 100,000 individuals both before and after housing costs) whilst the number of individuals in relative poverty has seen an increase (from 9.8 million to 11 million before housing costs and from 13 million to 14.5 after housing costs).

Source: DWP Households below average income, 1994/95 to 2018/19

Source: DWP Households below average income, 1994/95 to 2018/19

As well as these four measures, DWP produces statistics on material deprivation. This is where an individual or household can’t afford certain necessities and activities that are measured by a basket of goods.

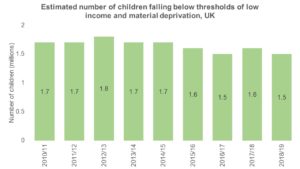

The DWP publishes estimates of the number of children falling below thresholds of low income and material deprivation in its HBAI statistics. The questions underpinning this measure were updated in 2010/11 and the DWP is clear that figures from the old and new suite of questions are not comparable. Since 2010/11, the number of children falling below thresholds of low income and material deprivation has fallen by 200,000.

Source: DWP Households below average income, 1994/95 to 2018/19

Material deprivation on its own is not widely used as a measure of poverty as it is not designed to measure low income. However, the combined measure of low income and material deprivation offers a wider measure of people’s living standards which can be used to look at elements of persistent poverty. This measure was the basis of one of the targets set in the Child Poverty Act 2010 aimed at reducing child poverty.

Outside the world of official statistics, there is another measure of poverty produced by the Social Metrics Commission (SMC). The SMC is an independent group of experts formed to develop a new approach to poverty measurement that both better reflects the nature and experiences of poverty that different families in the UK have, and can be used to build a consensus around poverty measurement and action in the UK.

It has been publishing its poverty measure since 2018 which is considered to be the most comprehensive measure of poverty available as it covers the depth, persistence and lived experience of poverty.

What more can be done to improve the evidence base on poverty?

The SMC has been working with the DWP to publish experimental statistics in 2020 that will look to take the current SMC measure and assess whether and how this can be developed and improved further to increase the value of these statistics to the public.

These experimental statistics will be published in addition to the HBAI publication, which will continue to produce the four recognised income-based measures of poverty highlighted earlier. The work on developing these statistics has been paused due to the Covid-19 pandemic but the DWP remains committed to carrying out this work.

Poverty remains a significant issue for the UK and has the potential to be of greater importance as we adjust to life following Covid-19. This is why we are launching a systemic review on the coherence of poverty statistics in Autumn 2020.

We will provide more information on the scope of the systemic review on our website later this year and we look forward to engaging with the public to understand how the quality and public value of official statistics on poverty can be improved, to help facilitate open and fair public debate.

The fact that there are different ways of measuring poverty should help build the bigger picture on poverty in the UK and should not be used as an excuse to be selective with data to support only part of the story. This is something the Chair of the UK Statistics Authority commented on back in 2017, when referring to the then Prime Minister’s comments on child poverty:

“We do, however, feel that public debate would be enhanced if the Government indicated more clearly which measure or measures it places greatest weight on and that it was consistent in reporting progress against this measure. It is unhelpful if there is regular switching between what constitutes the key measure.”

Measuring poverty is complicated. There is no wrong measure but there is a wrong way of using the available measures – and that is to pick and choose which statistics to use based on what best suits the argument you happen to be making. It is important to look at all the data available and set the context when referring to statistics on poverty.