In light of our first change to the Code of Practice, which relates to the release times of official statistics, and gives producers the opportunity to release statistics at times other 9.30am, where they and we judge that this clearly serves the public good, our latest blog sees Penny Babb – Head of Policy and Standards – look back over the first four years of the Code of Practice and consider its impact.

In some ways, time seems to have stood still over the last couple of years. But in other ways, I’m amazed it is only four years since we published Edition 2.0 of the Code of Practice for Statistics – how time has flown!

As I contemplate what the impact of the Code has been since we launched it in February 2018, my abiding sense is that the heart of the Code has never been better understood or more comprehensively applied. I know I’m biased, much like a proud parent sharing the latest pics of their child’s exploits, as I was closely involved in writing the Code and am OSR’s lead on its guidance.

I’m not sure there could have been a more profound test of the Code than statisticians needing to turn their work on its head and seemingly perform miracles – bringing new meaning to ‘vital statistics’. How easy it would have been to say in March 2020 that the ‘rule book’ needed to be ripped up as the world had changed.

Instead, analysts in the UK had a firm guide that supported and enabled them to make new and challenging choices – what to stop, what to change. How to better speak, explain, reach out to the massive audience with an insatiable appetite for numbers, to make sense of the unknown.

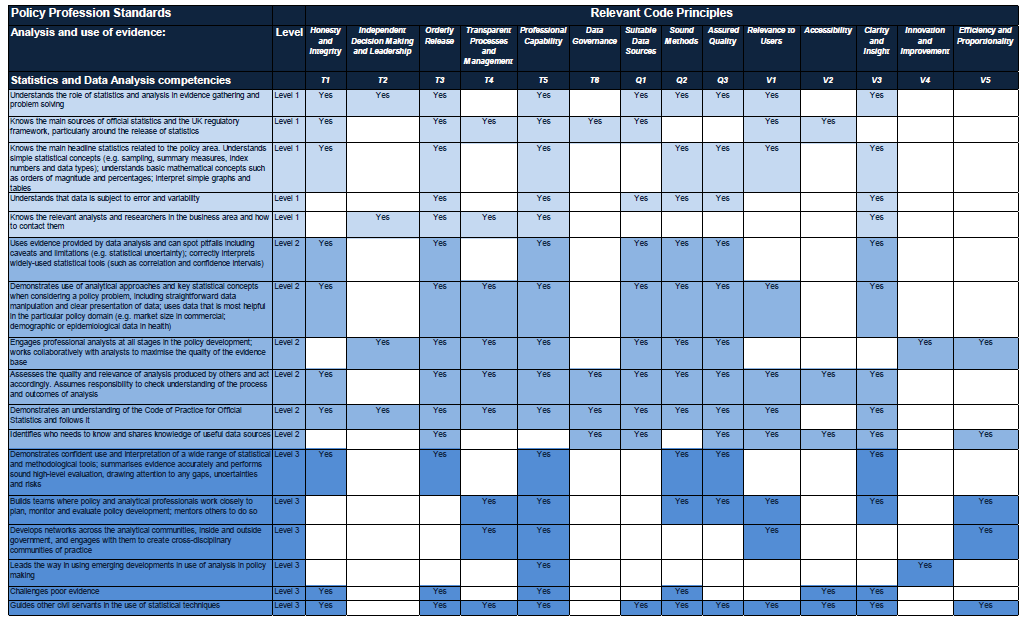

Underpinning their decisions were Trustworthiness, Quality and Value – the framework of our Code. For each dilemma faced, the answer lies in thinking TQV:

- What should I release – what information is needed right now to support decision making?

- How should I release it – how can you ensure that the public retains confidence in the statistics and the people releasing them?

- But there’s no time for ‘full’ QA – what information do you have confidence in that will not mislead?

Ultimately the Code of Practice is not a rule book but a guidebook.

Very little in the Code is a directive. One exception has been the practice setting out the time of release of official statistics as 9.30am (T3.6). Today we are changing this practice following our three-month consultation in autumn 2021 and conversations with producers, users and other stakeholders. With a focus on what is prime in enabling the statistics to best serve the public good, producers can now consider whether there is a need to release their official statistics at a time other than 9.30am.

There is nothing special about this specific time of day. The main characteristic is that it is a standard time across all official statistics producers in the UK that helps ensure consistency and transparency in the release arrangements and protects the independence of statistics. This is an essential hallmark of official statistics, and a norm that we continue to expect and promote.

However, as the pandemic clearly showed, there are some situations when a producer may sensibly wish to depart from the standard time. The new practice enables greater flexibility, but a release time should still depend on what best serves the public good.

We will continue to protect against political interference and ensure the public can have confidence in the official statistics. The final decision on whether an alternative release time is used will be made by the Director General for Regulation – the head of the Office for Statistics Regulation. All applications will be listed in our new table – it will include rejections as well as cases where the application was approved.

And there may be further changes to the Code of Practice to come this year. For example, our review of the National Statistics designation has already proposed changing the name of experimental statistics. So, watch this space for further developments. And if you have any reflections on the Code of Practice, please feel free to send them to regulation@statistics.gov.uk.